Welcome to new subscribers, and thank you to those of you who took out a paid subscription over Christmas. Every one of them contributes to me being able to produce high quality posts like this one, and to continue as a writer in the face of one of the most censorious periods in modern times for artists. If you appreciate what I’m doing here, please do take one out, or gift one to someone else.

Dora

There’s a lot wrong with me.

Saying it makes me ugly.

I don’t know how to say it. I

don’t know how to say

what has happened to me.

Alone I try not to remember.

The truth has shaped itself into a parody of me,

curled up in me like a baby,

a sinful, ugly baby

that cannot be loved, nor delivered.

The truth has no words.

Without words there can be no “facts”.

And Dr Freud wants facts from me.

Tell me what happened, he says. I offer him

My stumbling manacled dreams.

He says I’m in love with Herr K.

He says I’m in love with Frau K.

He says I’m in love with my father.

He says I’m probably in love with him.

Can’t he see what happens

when words confront the truth?

They scatter like rats.

They become non-words, non-sense.

I am dulled, as if a long stoning

finally is ending.

If I yield, he promises

there will be comfort.

I would like to be comforted.

Sir, we will do without the truth

we will do without it —

excuse my breathlessness as I stand,

my unsteadiness, my ugly limp. My body,

unruly thing, still tries you see

to say it, to push it out of me,

what happened to me.

Dear Subscriber,

Unspeakable: Freud’s ‘Dora’ and the victims of rape gangs.

An artist is a sort of emotional or spiritual historian. His role is to make you realise the door and glory of knowing who you are and what you are. He has to tell, because nobody else in the world can tell, what it is like to be alive.

— James Baldwin

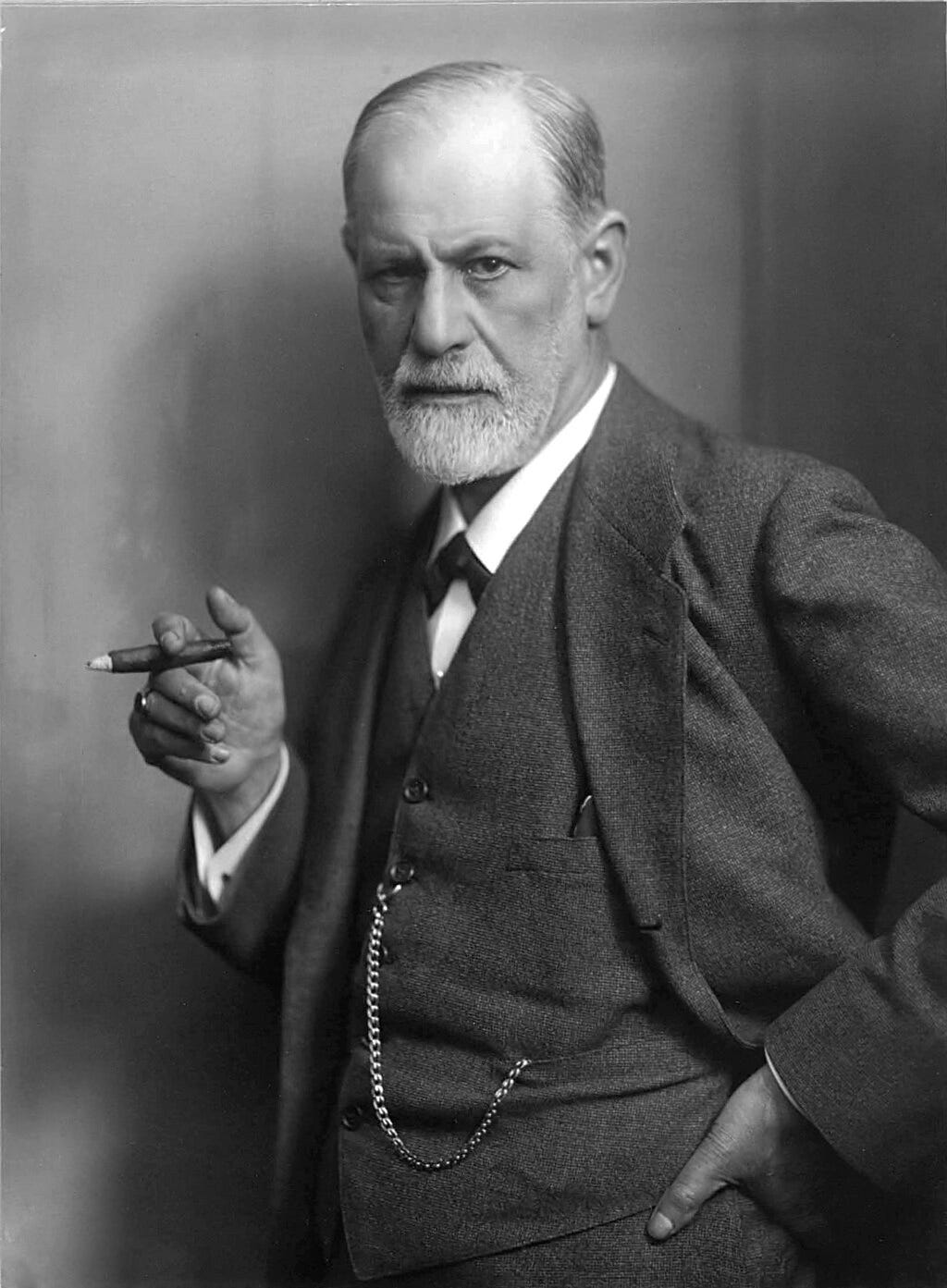

‘Dora’ was the name Freud gave to Ida Braun, an eighteen-year-old patient presented to him by her father. Her symptoms included loss of voice and coughing. During her treatment, Dora told Freud about her father’s affair with Frau K, the wife of Herr K, who were family friends. Dora revealed that her father had pressured her to accept advances from Herr K, advances that began when she was just fourteen. Freud agreed that her father was trying to legitimise his affair with Frau K by essentially bartering her with Herr K. Where the two of them differed — so profoundly that the teenage Dora broke off treatment after just eleven weeks— was that Freud interpreted the events as demonstrating that Dora had repressed sexual desire for both Herr K and her father.

This week, as the UK grapples with revelations about decades of child rape gangs operating in northern cities, the case of Dora feels starkly relevant. The same misogynistic and paedophilic belief that underpinned Freud’s interpretation—that young girls could consent to, and even desire, sexual relationships with adult men—resonates chillingly in the attitudes of the perpetrators, police, social workers, and judiciary involved in these crimes.

The child victims, some as young as twelve, were asked by police if they had "consented" to sexual activity. They were dismissed as sexually deviant “slags,” their voices silenced by systems meant to protect them. While Dora was a middle-class girl from a respected family and the victims of these gangs were often poor and from care homes, the shared societal trope is unmistakable: whatever the law says, young girls can consent, even to abuse. All that is required for such beliefs to flourish is license. Freud’s lack of outrage at an outrageous situation is what strikes the reader now. Just as those expected to protect these girls had no outrage at what had happened to them; instead being outraged that they should even try to speak.

Freud considered his treatment a failure. He puzzled over it long afterwards and later revised his analysis to include the possibility that Dora was primarily attached to Frau K. Like the victims of the UK’s grooming gangs, Dora spoke, but the authority figure in her life refused to hear and respond appropriately. Freud’s framework—like the biases of the police and others—imposed a false narrative on her reality. Dora’s bodily symptoms, expressing what her words could not, were pathologised as hysteria.

Dora’s decision to terminate treatment, rejecting Freud’s patriarchal distortions, strikes me as extraordinary. She may have given up on being cured, but she refused to accept the lie being forced upon her.

The struggle to be heard of Ida Braun and the rape victims are extremes of a narrative most women will recognise. It goes beyond merely trying to speak in the face of indifference. It is exile to a place of silence where the means of being understood are gone. In it I hear echoes of my own lifelong attempts as a girl and as a woman to communicate what it feels like to be alive using a language not designed for that purpose. I return to this ‘how’ of speech again and again: how to find words when the existing language is inadequate, shaped for purposes far removed from expressing my experience. It’s like trying to build a house with no bricks—needing to mine raw materials, fashion bricks from scratch, or borrow and repurpose the strangely shaped materials that make the palaces and institutions of men.

When I was around Dora’s age, I began writing a story about a mute boy. I wanted to explore my sense of being silenced as a young woman. But the story stalled. A boy need only look at pornography to see himself reflected as powerful. He need only pick up a history book to see himself reflected as heroic. He is, even without speaking, the inheritor of words, language, story and culture. By contrast, a girl, even one with full physical capacity to speak, is rendered mute when her experience falls outside the available language. So changing the sex of my protagonist, which can so often save a text from the chains of autobiography and bring in new possibilities had the opposite effect.

The story of ‘Dora’ resonated so profoundly with me that I named the heroine of my novel Larchfield, after her. My Dora is driven to despair by the roles imposed upon her. Her husband cannot hear her distress; her community turns against her. She finds solace by reaching out to WH Auden, who although freer by virtue of class, was similarly constrained in his expression of his inner world by the fact of his nature being criminalised. Their impossible relationship—across time and circumstance—offers Dora a lifeline. The key word here is impossible. Nothing in her real world can save her. Only imagination, poetry, a belief that her words are understood, can do that.

This is why the latest assault on women’s autonomy —gender identity ideology—feels existential. Exile from speaking about what happened has now morphed into exile from language itself. It’s as though the bricks I painstakingly fashioned to construct meaning have been set ablaze by marauders. They march forward, torches in hand, attempting to raze to the ground the concept of “woman,” the very foundation of what I am. This is the last frontier of misogyny: if the power even to name oneself is gone resistance against the extremes of violence is futile.

Continuing to write, to imagine, is a political act in such times. Like Ida Braun, I have given up on ordinary language. No one is listening, whether you’re a patient of the famous analyst or a broken girl from a care home. Only art, it seems, can transform the unspeakable into something that demands to be heard.

Thank you for reading,

Til next time, friends,

Polly x

You can catch up with all the Letters from a Poet here:

Check out this piece in The New Yorker about the relationship between thought and language:

How much does language change our thinking?

And finally…

Why not refer a friend to Monday Night Reads? There are complimentary gift subscriptions for you in return!

Share this post