I’m not a journalist or commentator and I don’t post ad-hoc in response to events; instead I craft each post to be an entertaining listen and read on a Monday evening. I love to think of us all connecting over a piece of writing at the same time each week (though of course I know you read and listen at other times). Sometimes my posts are topical, sometimes more reflective, but they’re always new and build to library of articles and readings you can return to.

If you have been forwarded this post, why not become a regular reader? The weekly posts are free. If you’re a free subscriber already, please consider taking out a paid subscription. It’s less than a fiver a month (even less with a discounted annual subscription) and comes with benefits that are real-world and unique to me. How many other substacks offer you access to a central London writer’s retreat? I’m thinking none. And you enable me to keep writing.

Islay

Thirty years ago, I’m sure you lifted

your eyes from her shore, and your gaze

drifted to this rock on the mainland

where I stand remembering you —

as today at the marina, when my husband

glimpsed the Innisfree, a boat he knew

long ago. Someone had made her new,

polished the years from her gleaming bow.

He fell silent as she pulled out to sea.

Just like that I think you’d know me now

as if the ocean, the islands, the sun between,

and all we love more had never been.

Dear Subscriber,

Outside Time: Writing and Longing

To be a writer is a life’s work, and as I get older, I see how I have channelled and worked through the same ideas in different ways since I first began scribbling as a child. It is strange, though, to see in a poem from long ago—written before I ever wrote a novel or set foot on a boat—the precursor to so much that is in Ocean.

When it came time to name the boat that carries Helen and her family through Ocean, there was only one choice: the Innisfree. This image from the poem ‘Islay’ surfaced immediately, inseparable from my husband’s memory of a boat he had once known. When our daughter was a tiny baby, we travelled up the west coast of Scotland to a place where we could see the inner Western Isles across the water. Islay is one of the largest of these. My husband, once a keen sailor, was unexpectedly moved by the sight of a boat he had known long ago. It struck me then, and even more so now as I live on a boat and have sailed the open waters, how vessels hold not just memories but time itself. Boats are like time machines.

In Ocean, the Innisfree becomes a vessel for healing the present by recreating the past. Time in the novel is a strange, permeable thing. On land, time governs our days relentlessly, yet on water, it is both eternal and simply mathematical — essential for navigation. On water, ‘time’ and ‘space’ act out their continuum.

The poem ‘Islay’ contains its own shifts in time. A dear friend of mine, long ago, was a fisherman off the island of Islay. I did not know him then, but in the poem, I imagined him looking across the years to see me standing on the mainland, as if history dissolved and our connection existed beyond time. In those three short stanzas, the poem suspends time from several different perspectives, in a kind of cubism, all connected by longing.

is sense of being untethered from the ordinary flow of time is in Ocean as well. At sea, the family is disconnected from everyday life. The absent and the dead feel as present as the living. Time no longer divides but connects, pulling moments together into a deeper, elemental rhythm. Longing becomes the force that brings things into being, whether for a moment or a lifetime.

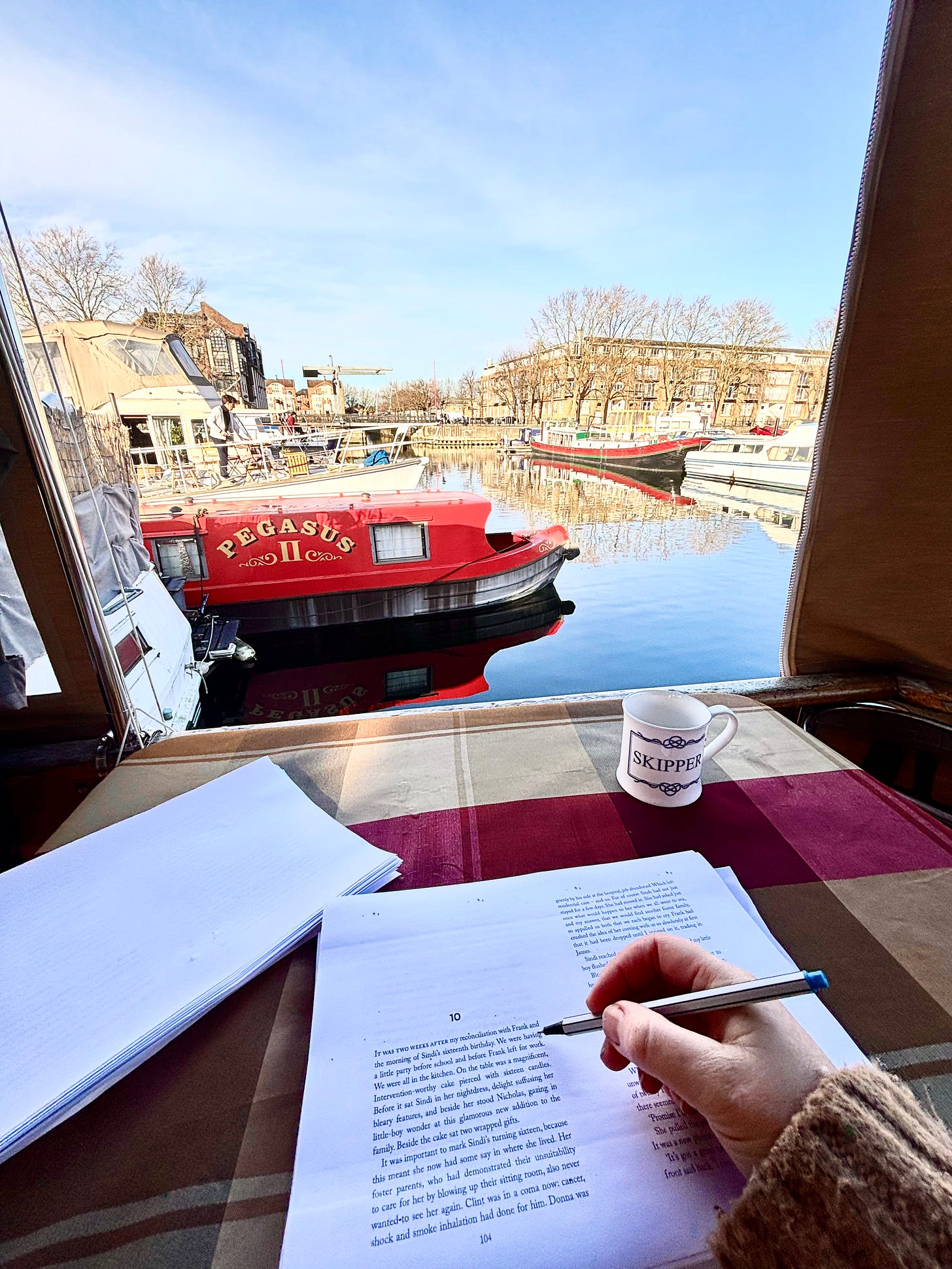

Currently, I am correcting the galleys of Ocean, which comes out in June. This stage of the publication process is, for me, the most enjoyable. Seeing the story in proper print forces fresh eyes upon it, revealing nuances I might otherwise miss. The challenge, of course, is not simply to “read” and get swept up in the story. One of my subscribers,

suggested reading backward—from the end to the beginning—and it’s proven a remarkably effective way to keep my focus. Reading in this way alters perspective, breaking the usual flow of time within the story and revealing layers that might otherwise remain hidden. It’s a reminder of how reshaping time, whether in writing or in life, can bring new truths to light. Proofing cannot be hurried, and I’m grateful for the chance to linger in this liminal space, untethered from time, much like writing itself.This is a moment when a book hovers between the internal, creative world it was born from and the external, physical world it will soon inhabit. Publication and writing are entirely different worlds—universes, even. Aspiring writers, and indeed all writers, crave publication because a writer is nothing without readers. But publication is external; writing is internal. And here, in this threshold before Ocean is released, I find a blissful balance. The book is as close as it will ever be to the dream I first imagined, and the world has yet to impose its expectations upon it.

Poetry, by contrast, exists entirely outside such expectations. It is pure writing. There isn’t the same demand for “results,” and that purity is something I strive to rediscover with every piece I write. A poem is always done for its own sake. It operates outside commerce or expectation. No one admires a poet at a dinner party, and they certainly haven’t heard of you. But in return for this obscurity, poetry offers something extraordinary: the pure, wordless high of capturing a truth, carving it into permanence.

The longing in ‘Islay’—the sense of the unlived being as real as the lived—echoes throughout my work. The boat as a metaphor for time and memory, the malleability of the past—these are truths I carry in my marrow. They shape every word I write, from poetry to prose.

Every writer has their subjects, and one of mine is longing. It is a sustaining force, though not without its costs. Longing has generated all my work and shows no sign of being exhausted. Even if, sometimes, I am.

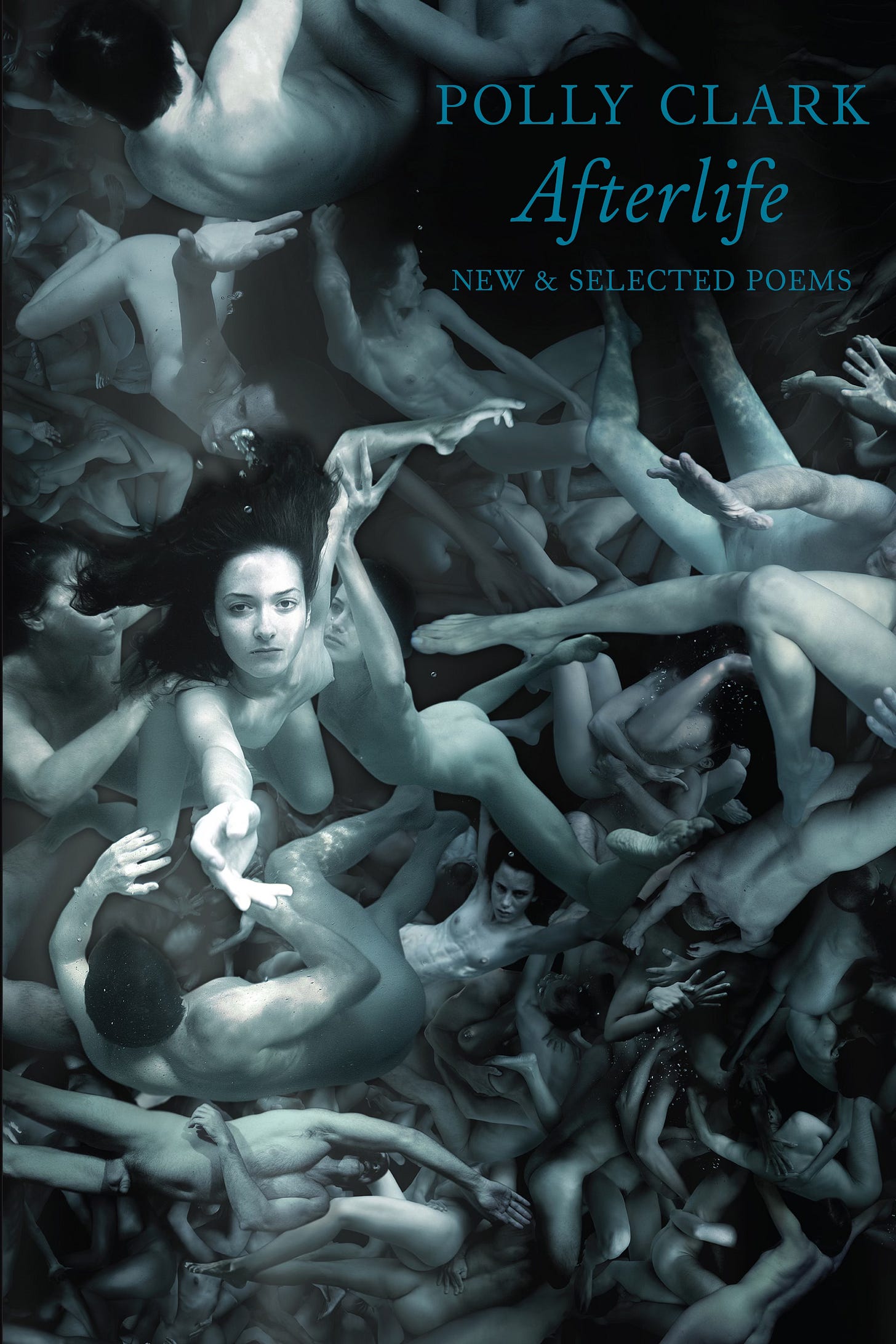

In another convergence of past and present, ‘Islay’ will appear again in Afterlife, my New and Selected Poems, coming out next year after Ocean. To see the novel and my poetry side by side feels remarkable, as if all my works—despite spanning thirty years—are alive in the same moment. As I grow older, this is what astonishes me most: the way time folds and unfolds like a wave, offering glimpses of the eternal.

Living on a boat, I’ve come to understand how while they carry us forward, they are also steeped in the past—their histories etched into every plank, every line, every scrape. The Innisfree in Ocean does the same. It is a place where memory and the present connect and even interact, where the family can confront their grief and channel their longing. For me, writing is not so different. Each poem, each novel, carries traces of who I have been, yet each is its own journey, pushing toward something and someone new. That sense of movement, of discovery, is what keeps me writing, and what makes it feel, always, like I am stepping outside time.

Thank you for reading,

Until next time, friends,

Polly x

If you have enjoyed this Letter From A Poet, you can view the whole series here:

And finally…

My hometown of Helensburgh, and the setting of my novel Larchfield was hit by storm Eowyn this week. This is the roof coming off the brand new sports centre. A very sad day for this lovely historic town.

See you next week!

Polly

Share this post