A Loving Call to Action

There are many small actions you can take that help to spread the word and support Monday Night Reads. Will you take one today?

First up do share this post if you’ve enjoyed it. Lift a quote you liked, share a comment, restack the whole post!

You can refer a friend easily with this button. And if your friend becomes a free or paid subscriber, you get rewards! It’s a win-win, and we all like those.

Why not gift a subscription? There’s 20% off a year with this button. A lovely literary gift, and support for an artist.

Brief Encounter

I never knew you, though

I wrote page upon page about

how you would feel inside my heart

and in my pen, and how

my life would be corrected

by the ballast of you in my gut. But

I never saw you though I searched —

in the eye whites of the gypsy, in

the smiles of people who never asked anything of me,

in traces of blood, flakes of skin,

one long curling hair which lay between

my pages. They all made words line up neatly in my mind,

but where were you? My authenticity,

the soul of everything I meant to say,

where were you, I never knew you.

Until today. I stood beneath the hot stream

of water, washing away my headache and hatred

for hour after hour, and then, in a drop on my eyelash,

I saw you move, I saw you move! I saw

your shiny black carapace

shrinking beneath hot tears of water

and your fat black legs

lumbering to safety. It was not what I imagined,

grief. Nor the convulsive reaction,

the terror, the urge to survive,

the roaring and stamping in my head,

the smell of heat and hallucinations, the voices,

bury the dead, bury the dead.

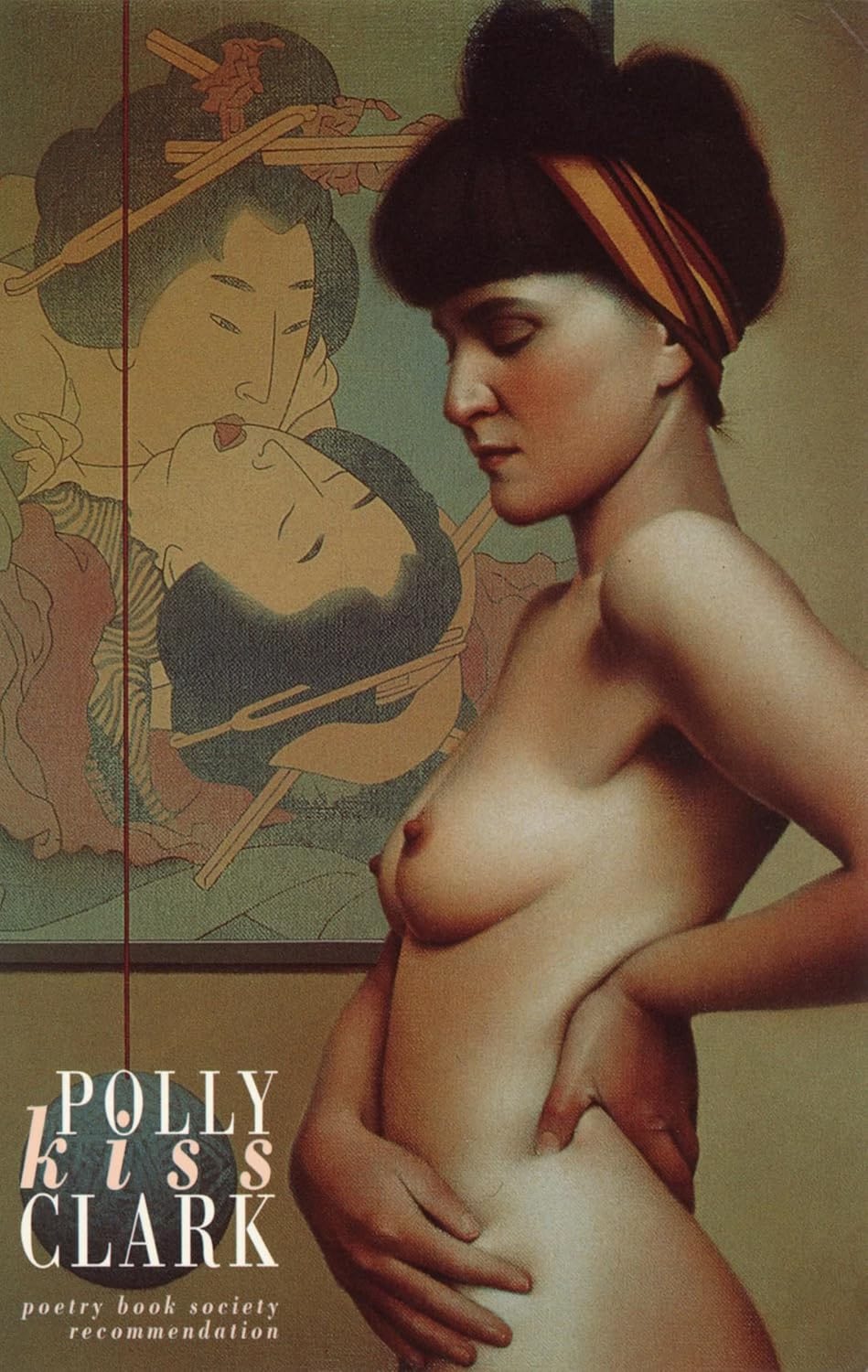

Dear Subscriber,

In another Letter From A Poet (Letter Nine: Lily Philips, lies and poetry) I described my brief foray into the porn-writing industry—a detour taken by an unremarkable graduate from a middling redbrick, desperate for any journalism job that would have me. Six months proved to be my limit for that work. One day, I awoke in my grimy flatshare and, stepping out of bed onto a forgotten fork (a remnant of my exhaustion and depression), squealed in pain and thought: this is over.

I went into work and handed in my notice, relinquishing not only my job but also my room in that dismal flatshare. A former tutor casually mentioned that another student of his was teaching English in Hungary, and without hesitation, I asked to be put in touch—by letter, for we had no email then. One lunchtime, I queued at the travel agent and bought a one-way ticket, by boat and train, to the small town of Pécs on the border with Croatia. There was no point in planning a return; I had nothing left to go back to.

My final salary, by my calculations, would sustain me in Hungary for six months. I didn’t think beyond that—either it would work out, or it wouldn’t. In a little charity-shop suitcase, I packed ten hefty books I’d long meant to read—Master and Margarita, Crime and Punishment, Unbearable Lightness of Being among them. I gathered mix tapes from friends and family, my trusty walkman, paper and pens, The Rough Guide to Hungary, and a few changes of clothes.

I had no phone, no address—the next anyone would hear of me was notice of my poste restante. My life and its attachments slipped away peacefully like ripples from the prow of a boat. On the ferry from Dover, I looked back at the cliffs and mused—if dying is like this, then perhaps I’m ready for it.

It wasn’t until I awoke in Germany, with the Danube shimmering beside my window, that I finally checked where I was headed. I was stunned to learn how far Pécs truly lay. Consulting the glossary at the back of the Rough Guide, I realised the language was impenetrable—a Finno-ugric tongue sharing more with Welsh than with anything I knew. In a café in Vienna, waiting for my train to Budapest, I practiced the three Hungarian words I’d manage with for weeks: Igen (yes), Nem (no), and köszönöm (thank you). Like every other means of contact, language became an essential I no longer possessed.

Gradually, I was departing the world I had known, venturing deeper into a strange dream. Was I afraid? Not in the slightest. In that life-dying state, fear held no power. I was throwing myself upon the mercy of the world: in response it caught me, transforming my existence into something that felt magical.

In hindsight I was fleeing both fear and grief. Later that summer, I found myself at the public swimming pool—the lido at the far end of town—where the heat was drowsy and pregnant with the rain of the season. After months of stress in London, my skin had erupted in painful acne along my back. I removed my shirt and lay in the baking sun. I must have appeared an odd, unappealing sight to the beautiful young Hungarians chatting and playing by the pool, but my lack of comprehension shielded me. We were all about the same age—I was 22—but they seemed like a different species. All day, the sun caressed my sore skin, healing me, and for the first time in years, I relaxed. A week of pool visits, sleep, gentle swimming, and endless reading began to cure me. I began to feel again

.For three long weeks, my planned rendezvous with my tutor’s contact failed to materialise. I stayed in a modest hotel, navigating my days with my three Hungarian words and a few German phrases. Pécs revealed itself as a beautiful town; I walked, read, and wrote ceaselessly. At night, vivid dreams pursued me, as my mind, starved for conversation, overflowed with words. I could devour a big novel in a day, filling notebook after notebook with my thoughts. This was before I even acknowledged myself as a writer—before much had been published beyond pornography. I was becoming a poet before my own eyes, swirling images and thoughts onto pages.

Yet, the essential feeling that had driven me to break free—sadness—remained unexpressed. I hadn’t cried in years, priding myself on my resilience. My life until then had been relentless: tracing my father and discovering his cruelty, feeling alienated from my family, learning of my sister’s struggle with addiction. There was never a moment to process it all. In this strange and lovely purgatory, my writing circled these raw experiences, as I struggled to feel, to process, not fully understanding what was coming.

As the poem suggests, overwhelming grief and fear are two sides of the same coin. I had believed that feeling my losses—allowing myself to cry—would animate my writing. Instead, the thought terrified me. The poem transformed into a primitive chant, a ritual against annihilation, as I invoked both the terrible genie of grief and my defence against it with rhythm, ritual, chanting, and drums. This was the very birth of my poetry.

Years passed, and the echoes of my internal transformation faded. Then fate intervened to bring it back in the most unexpected form. It was a decade after this experience, and after publishing my second collection and establishing myself as a poet, I had the privilege of presenting the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Richard Ford on a tour around southern England. I had not yet written a novel, and I was in awe of Ford’s mastery as a writer, the power of his intellect, and the resonant timbre of his voice. One of our dates was in Brighton—a grand, packed venue. When he stepped onto the stage, to my astonishment, instead of reading an extract from The Lay of The Land, he read ‘Brief Encounter’ to the assembled audience.

Hearing my poem read with such authority brought it powerfully alive once more. The struggle to forge art from the deepest of emotions is an existential battle, and the control offered by a poem becomes the writer’s weapon, their hope for survival. Ford’s reading aloud of ‘Brief Encounter’ revealed it as a story of courage wrought from an encounter with terror—the courage of the artist in the face of the overwhelming forces of the human soul.

Thank you for reading,

Until next time, friends,

Polly x

You can catch up with all Letters From A Poet here:

And here is Letter Nine, referred to above:

Share this post