If you have been forwarded this post or come across it as a follower, why not subscribe? Every Monday all my subscribers, free and paid, receive a poem and specially written letter in which I explore the wider issues raised by the poem, its background, and the writing process. If you appreciate my work here, do please take out a paid subscription if you can. You are supporting an artist directly and personally. I appreciate every one.

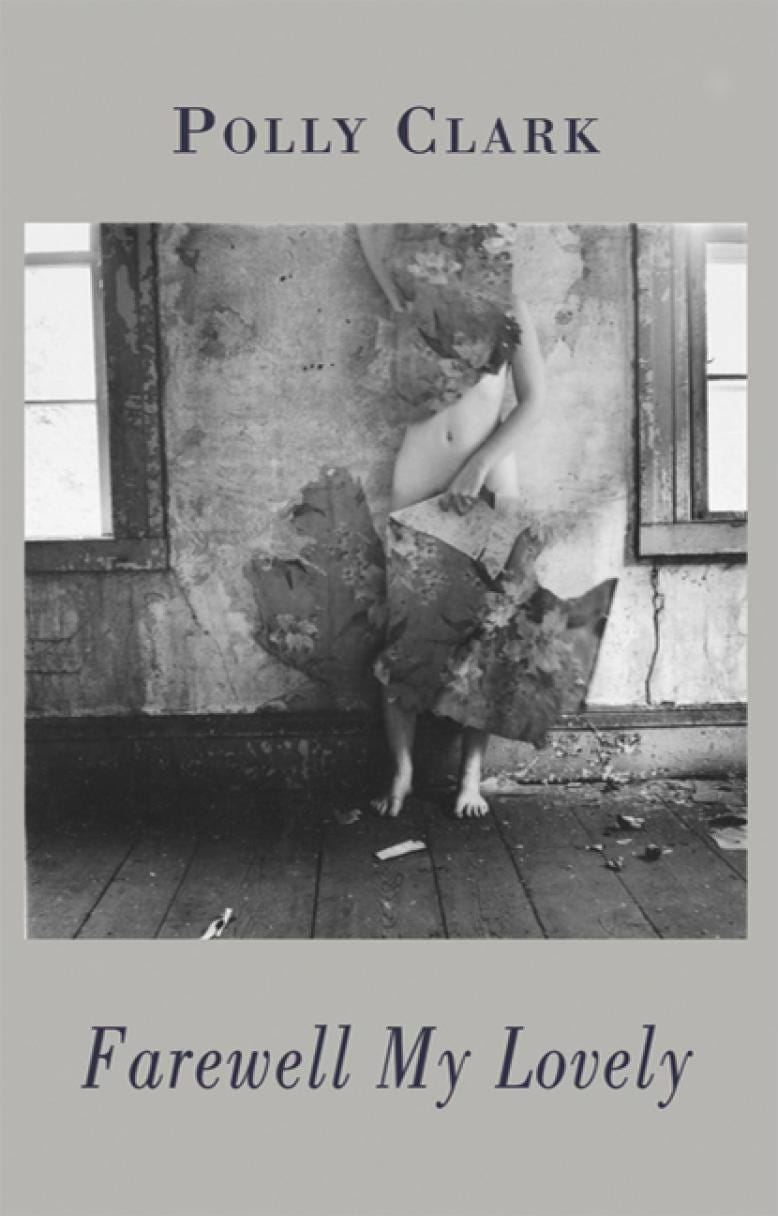

Farewell My Lovely

‘A really good detective never gets married’ — Raymond Chandler

I’d gotten used to that roomy grin,

the face like a bag of facts,

the flank round as a pony’s

and the way she had of blending in

so badly. But after all,

I didn’t really know her

neither she nor I being the intimate type.

I take a slug of something

that I’ve been craving, make a note

of everything that’s gone with her.

But my notes become a list

of immoveables: this slouching house,

the sea with a face I’d like to smack,

the loosening sky, fit to drop —

as I’m dusting the mirror

I glimpse her, smart as rat

in the company of rocks —

but the day’s slammed shut

and it’s time to file the file.

This is a face to be turned over

for answers from now on.

She’s left nothing behind her

to show what was between us.

Always meticulous,

I find she’s slipped

like a last dram into my dreams,

hunched at the scene, wiping fingerprints,

knowing that’s over, that it’s time to go.

Dear Subscriber,

The Case of the Missing Self

In The Second Sex, Simone de Beauvoir writes, “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.” This quote has been heavily abused by gender ideology activists to promote the notion that a woman is nothing more than the accumulation of stereotypes that anyone, including any man, can perform: hair, makeup, mannerisms, dresses. This is not what de Beauvoir meant, of course. She meant that a woman is born a female human, nothing more, nothing less. Then society gets to work forging her into a ‘woman’ by impressing upon her the roles it requires for its continuance. This applies to men too—a ‘man’ is made by society from the starting point of ‘male baby.’ But the processes are not equal. The socialisation of men teaches them to embrace independence, authority, strength; while a woman is taught to be relational, to give.

One can imagine why it is tempting for either sex to escape their straitjacket. So deeply are these roles ingrained in culture and society that, for some, it has seemed easier to alter their bodies to escape the roles than to challenge the roles themselves.

This notion of escape is at the heart of ‘Farewell My Lovely'. The poem is cast as a moment in a detective story for a reason. Its title is not just the title of Raymond Chandler’s famous novel, whose tone I have emulated in the poem, but also the title of the entire collection, because constraint and escape are themes running all through. The tone is poignant, because a loved part of the self has gone, but there is something else underneath—something more defiant. A dash of rebellion, impossible to pin down. A deliberate slipping through the cracks.

The detective in the poem is supposed to solve things, but he does not try very hard. Perhaps he sees the empty space where she used to be and knows that it’s best left unsolved. A good detective recognises when the fugitive deserves their freedom. Or maybe he suspects that she is still out there, just beyond the frame, watching him, smirking slightly as he dusts for prints that aren’t there. Perhaps he even envies her escape.

But what of the detective? Left behind, ‘his’ role is to create a narrative, be reasonable, have the answers. There is a sense that he, too, is trapped. Perhaps he is not simply letting her go—perhaps he is glad to see her disappear. Perhaps it removes the disruption; at last, there will be peace. Isn’t this why troublesome women are bumped off in the old detective stories? They won’t stop speaking the truth, they won’t stop needing, wanting, talking.

I realised subconsciously very early that what I was required to be — helpful, attentive to others, giving of my time and my labour — was antithetical to the self-assertion of an artist. And what I actually had to give—the entirety of myself through my work—was not valued at all. My struggle with this is characterised by others as being difficult and demanding; my pointing to the political machinations beneath it called out as bigotry, lack of femininity.

The famous quote attributed to Jane Austen—‘I am neither man nor woman, but an author’—captures the lifelong battle to assert such a claim. This simple statement belies the relentless effort to keep working when you know that the world would be perfectly content if you went back to doing what you’re supposed to do. Austen did not marry, and she understood only too well what was at stake in a traditional marriage. The stakes are existential, which is why her supposedly quiet books read like thrillers for those who understand them.

To fight for your own individuality and self-expression as a woman in a world that does not value it is exhausting, and this is why so many women give up. It is extraordinarily painful to continue with the loneliness of asserting I in a society that demands I subsume myself into we. This poem delineates that attempt very clearly. The detective is the internalised compliant, respectable self. The free spirit, the artist-self, has fled the scene, or perhaps has even been killed. The poem seems to say: the price of being recognisable, respectable, of having a place in the world is to lose, even destroy, the creative part of yourself.

We like to think we can reinvent ancient cultural structures—marriage, gender roles, societal expectations—but their grip is stronger than we admit. They constrain us all, men and women. But for women, whose societal roles have been built around their bodies, around the handing over of actual life-years to others, resisting these roles often means exile from the familiar forms of belonging, from the easy acceptance that compliance affords. A man must break laws, rampage through life to be cast out. A woman need only refuse to comply.

The needs of the artist require a kind of selfishness—but only in the way that survival does. To create something that speaks to others, to give the truest part of oneself to the world, an artist must first claim it. And yet, to belong, the pressure is on to relinquish that part of the self that holds these unacceptable needs—the need to take up space, to speak without permission, to prioritise creation over compliance.

And so the self is divided. But was ‘she’ ever truly gone? She wrote the poem, after all. And she’s here, now, in these words, reaching out to tell you her story. And perhaps the detective, standing in the dim light, understands—perhaps he, too, has been searching for something all along. Maybe he realises he is no longer chasing a fugitive, but looking at his own reflection—another figure bound by expectation, longing for escape. Maybe, just maybe, he will follow—leaving behind the script he was handed and stepping with her into the unknown.

Thank you for reading,

Until next time,

Polly x

This post is public, so please feel free to share:

You can catch up with all Letters From A Poet here:

And finally…

Monday Night Reads is a regular, consistent and unique text delivered to you every Monday at 7pm. Thank you for reading, and do please take out a paid subscription if you can. Every single one contributes to the growth of this site. Alternatively, please share and tell your friends! Referrals bring complimentary subscriptions for you.

Share this post