We are the notorious scapegoats, for confessing openly what others only confess to doctors under guarantee of professional secret. We are also underpaid: people feel that we are in love with our work, and that one should not be paid for doing what you most love to do. — Anais Nin

In these censorious times, artists need patrons more than ever. Your support has enabled me to create some of my best work via this substack. A paid subscription comes with great benefits, and keeps me writing. At present it is my only source of income. If you appreciate what I am doing here please take out a paid subscription, or buy one of my books!

The Walk of Faith

can stand the weight of five baby elephants.

I cannot do it, I cannot cross a square of glass

though you hold my hand though you

point out that I weigh less than five baby elephants.

It is not the fear of falling,

but the fear of disobedience —

of walking where I was not meant to walk,

of seeing people tiny vulnerable,

without civilisation or meaning.

I have no faith: I could not cross and be unchanged.

The source of my giddiness: I am a speck in the sky

and no one remembers me. And at the same time

I know the tiny scattered creatures

whom we observe with mild loathing

and some pity are me. They are all me,

running without direction, as if I had plummeted through

the five-baby-elephant-proof glass and had

shattered on North Shore and all the pieces

had picked themselves up and were scuttling away.

Look — that one crosses the road a little too recklessly,

is narrowly missed by a tram, is tearing away from something.

There — another has flung her arms around a man in the street,

a man whom she thought was her father,

and indeed he seems not unwilling to take on the role,

he has embraced her, he is kissing her hair,

telling her I will try anything twice and laughing.

But look there: a crowd has gathered,

a circle around somebody dead in the road,

it’s someone whose hate has got the better of them,

someone who’s gone and got themselves killed,

and somebody’s sister is sprinting towards the Pleasure Beach

— I can see from here that she’s not going to make it —

the crowds are gaining on her, the swoop of the Big Dipper

is impossibly far away —

that other place, where people fall and do not break,

I cannot reach it, no faith I know of

can get me there.

Dear Subscriber,

I will try anything twice

Decades before Blackpool became synonymous with the BBC’s Strictly Come Dancing competition, it was the holiday destination for many families in north-west England who couldn’t afford trips abroad. Freezing sea, windbreakers, kiss-me-quick hats, and sticks of rock were its staples. If you were very lucky, you might visit the Pleasure Beach and ride its fabled Big Dipper. My grandparents lived there, and their house and those trips to the beach are woven into my 1970s childhood memories.

In 1998, Blackpool Tower was refurbished with new attractions, including the ‘Walk of Faith,’ a glass panel at the top through which visitors could view the promenade beneath their feet. Years later, after a long absence and with a world of distance in between, I returned to Blackpool for a visit, showing my roots for the first time to a boyfriend. We travelled to the top of the Tower to try the Walk of Faith for ourselves.

Blackpool is in my bones. My grandmother, after whom my daughter is named, lived in a tidy 1930s semi about a mile from the promenade at North Shore, with her husband Fred. They had married in Oldham during World War II (Fred was not conscripted because of bad lungs) and settled in Blackpool. My grandmother was a Methodist by upbringing, her own father a minister in the church. Though she didn’t seem religious, there was a spartan, abstemious side to her character and their lives that may have come from that heritage.

I think her married life was hard. When Fred had a stroke in his seventies, his personality changed—or rather, hardened. She once told me privately that she was unhappy, that he hit her. He used to whistle at her to come to him, like a dog. “Leave him,” I said with the moral certainty only a twelve year old can have. She shook her head. “But where would I go?” Nobody left anybody in her day, and I am sure the constraints of respectability held her tightly in place.

I loved her. She wasn’t demonstrative, but she kept my secrets, offered kind counsel, and when, at nineteen, I embarked on a search for the father I had never met, she was the only one who helped me.

My father was never spoken of in the family. It was as if I had been immaculately conceived. But I became obsessed with knowing who he was. Finally, I traced him, using only the dates my grandmother gave me and some wedding photos my mother had hidden in a drawer. He invited me to London, from Liverpool, where I was studying, and we met at the top of the escalators at Euston station.

The extraordinary thing was that this meeting took place when I was nineteen—the same age my mother had been when she married him. He plucked her out of her northern obscurity in Blackpool before abandoning her. And he did the same to me. “I will try anything twice,” he said. I did not hear the warning implicit in his words, that nothing was truly real to him; nothing meant anything to him. He was jubilant in chaos, a showman who thrived in beginnings.

Finding my father gave me answers, but no resolution. In retrospect I was shattered, like a stick of rock, and when you break it open, all the people in my life come running out. This, to me, is the sensation of vertigo, which this poem tries to express and create in the reader. Faced with the challenge of faith presented by the glass, the speaker’s sense of herself as a whole person crumbles. How fragile that faith is, how easily broken; and look what’s inside me —chaos.

My father had no sense of obligation or responsibility. He was handsome, dashing, and rich, with a big house in London, while we had struggled against poverty. He had never paid child support or tried to see his children. My mother was a single parent by 1968, abandoned while pregnant with me. The shame brought on her parents must have been enormous.

When I found my father as a hopelessly romantic nineteen-year-old, I fell for the glamour of him as surely as my mother must have done a generation before. But he told me he was incapable of feeling guilt. My older sister never recovered from his abandonment, struggling with addiction for much of her life. My mother told me I must choose between them. I couldn’t give him up, as stubborn in the face of disapproval as she must have been when she first brought home the “flash southerner” to her stiff, awkward parents. I have been estranged from my mother and sister for many years. Only my grandmother would hear his name; only my grandmother understood

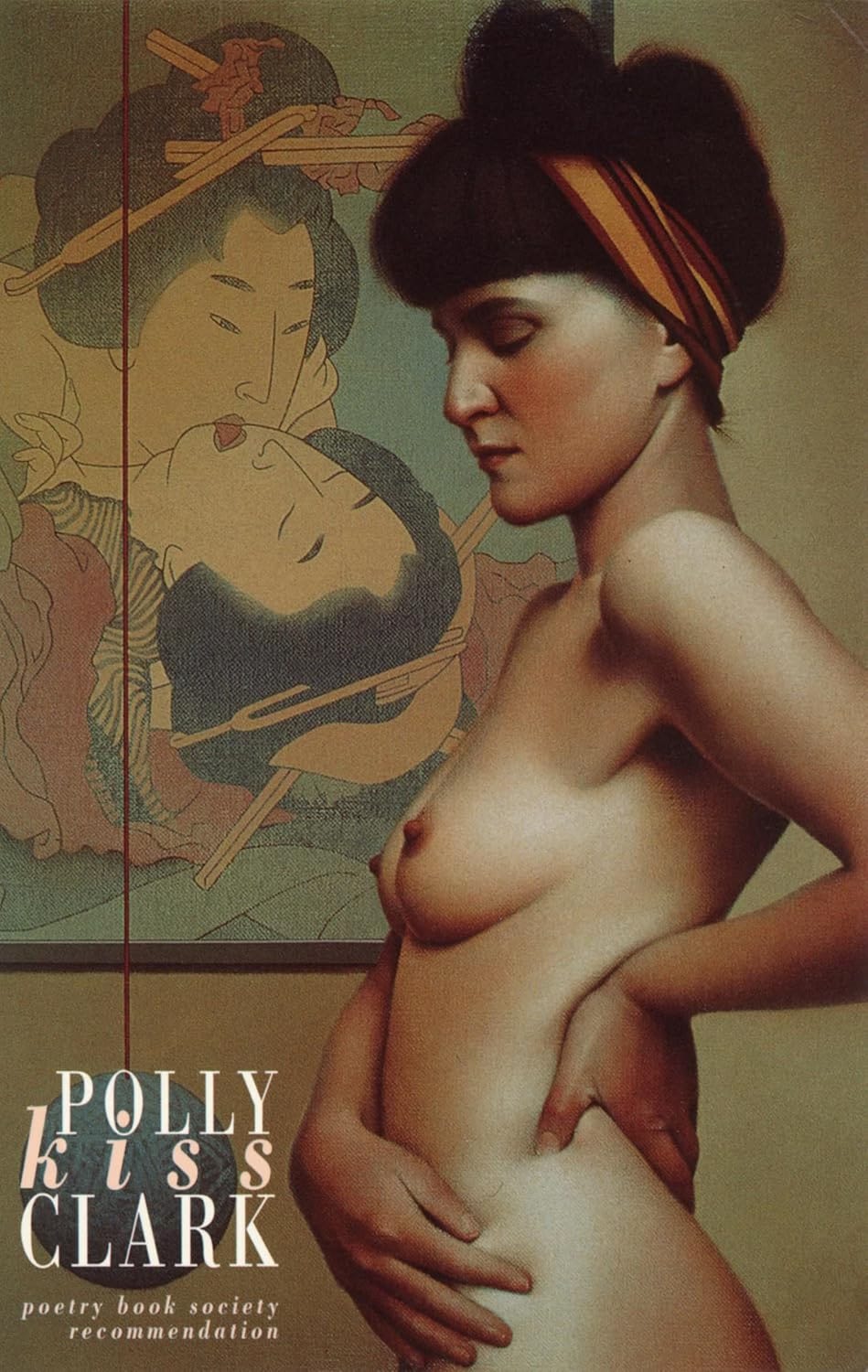

Shortly before this poem was published in my debut collection Kiss, when I was thirty, my father unexpectedly died. The decade I knew him was a decade of torment. Nevertheless, when he was gone, I was devastated. I was alone in my grief, of course, because my mother was glad. I think I thought I had integrated him into myself, that I had worked through what my father meant in my life. But this poem shows how little we integrate, how little we work through. That is the terror of vertigo in this poem: the glimpse of meaninglessness. All that pain—and for what?

Where my grandmother clung to respectability as a lifeline, my father rejected responsibility entirely, leaving others to piece together what he had broken. Crossing a glass walkway is an act of faith in the unseen, in the structure that holds you up. I have always struggled to believe in the invisible bonds that hold us together as individuals, and as families.

I can’t remember if I did cross the Walk of Faith in the end. A few years later, my grandmother died too, and I never had reason to go back to Blackpool.

Many years after that, I crossed another glass walkway—a grand one at Tower Bridge, this time with my own little girl, named after my grandmother. She skipped along it, delighted. But she had her mother there, and her father, and relatives on my father’s side who had survived the wreckage of those years. There was nothing for her to be afraid of. I like to think of that as my life’s work, over and beyond the writing of a poem: that my daughter should have a healed life, a safe life, a life in which she can have faith.

Thank you for reading,

Until next time, friends,

Polly x

If you enjoyed this Letter From A Poet, you can catch up with them all here:

Support me by buying great books through my bookshop

Favourite reads, my own novels, books by subscribers, books featured on Monday Night Reads — they’re all here in my bookshop.org shop. Every purchase made through my specially curated shopfront generates a small commission for me, and also raises money for independent bookshops.

My poetry collections can also bought via my publisher, Bloodaxe Books. I don’t receive a commission for this, but you help my publisher survive.

And finally…

Invite your friends and earn rewards

If you enjoy Monday Night Reads, share it with your friends and earn rewards when they subscribe.

Till next week, friends!

Polly x

Share this post