Full disclosure: I used to work in the porn industry. Not as an actor like Lily Phillips, but as a writer for Paul Raymond Publications—the now quaint-seeming pornography empire run from Soho, London.

Letter to the Man I Love

When feeling cheated, remember

that you are loved

by the only one who didn’t cry.

This may seems small consolation,

and perhaps you prefer you were not loved by

someone of such monumental achievement.

Please, let me explain.

I have watched as people are stripped naked

and invited to writhe on the floor.

I do not know them, nor

what they may have done to deserve this.

I have, however, invented names for them, and stories

about how much they enjoy it.

I have filled their mouths with lies,

and I have answered letters from the general public

as if I were them, repeating those lies.

I have written their confessions

which were totally untrue

and received payment for the forgery.

I have given, on request,

photos of them in various poses to friends

and even to my own father (who was delighted)

in order to make myself more popular (which it did).

I have, on social occasions announced

That my varied tasks I find ‘liberating’,

and on that basis have found myself,

on more than one occasion

embodying those lies.

I have answered phone calls from the general public

who wish to know in exactly what way

I would like to be stripped

and pushed to the floor,

with scrupulous politeness,

following the company code that all callers are customers.

I have not, until now,

questioned out loud

the glaring fact that all these people

stripped and lied about

are not unlike myself, and that I

have written about them as if they were dogs or mice

because that is the only way to lie about them convincingly.

Nor have I, until today,

when I couldn’t stop crying

realised the impossibility of love

with someone to whom

I have lied so much.

Dear Subscriber

A Letter about Lily Phillips, Lies, and Poetry

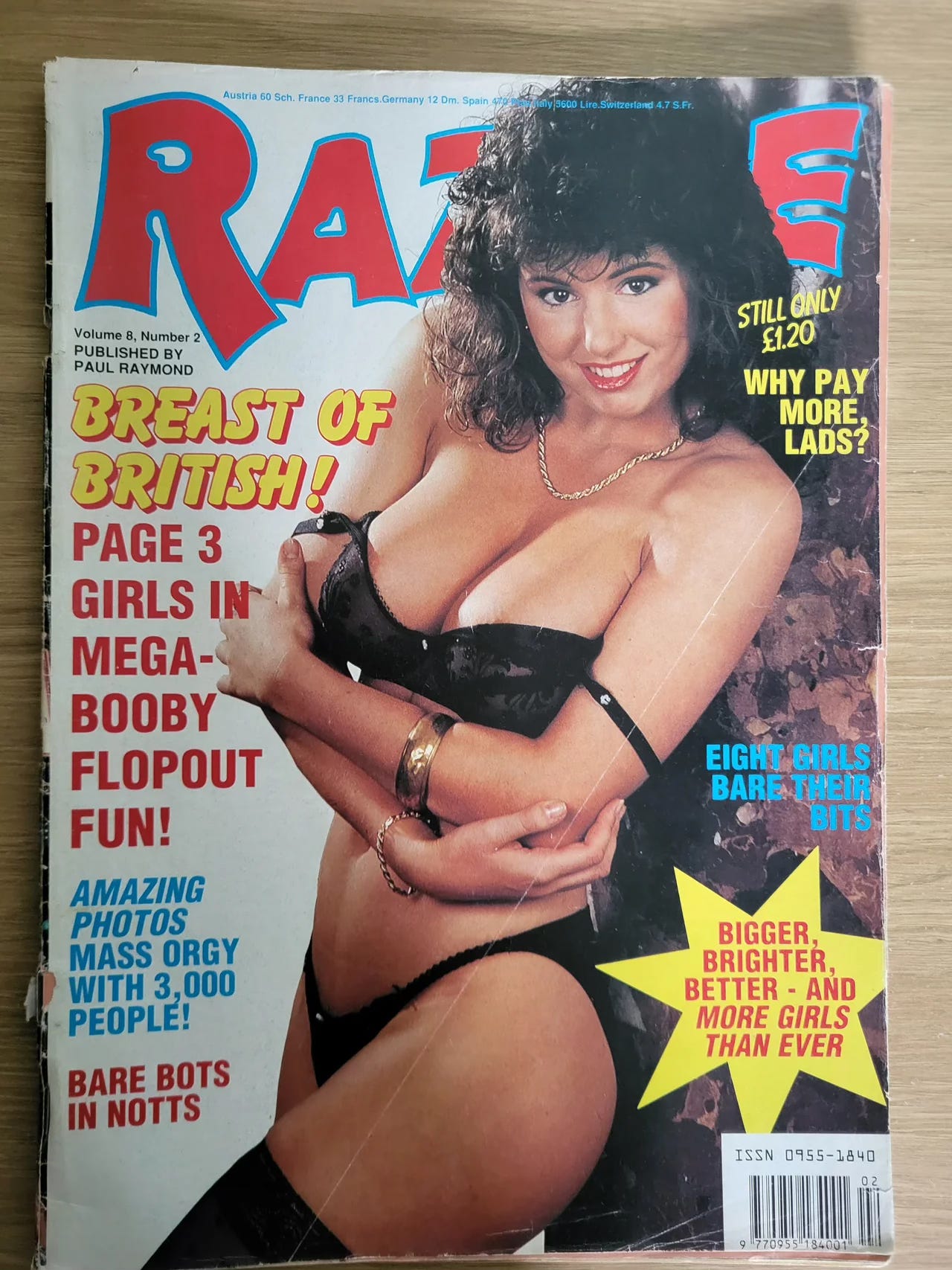

Full disclosure: I used to work in the porn industry. Not as an actor like Lily Phillips, but as a writer for Paul Raymond Publications—the now quaint-seeming pornography empire run from Soho, London. My job—possibly the hardest I’ve ever done, aside from caring for zebras as a zookeeper—was to manage the relentless publishing schedules for three top titles: Mayfair, Club, and Razzle. I also wrote ‘confessions,’ letters, and photo stories in the distinct style of each magazine.

Yes, there was a time when pornography was printed on glossy paper, and a man had to walk into a shop, buy it, and look the assistant in the eye as he did so.

Why was I doing this job? The first reason was desperation. The early ’90s recession in the UK was so grim that it was the only job a young unconnected woman with a middling arts degree and hopes of breaking into publishing in London could get. Second, the job advert made no mention of pornography. In The Guardian jobs section, which I combed for hope every week of my agonising post graduation life, there was a photograph of Arnold Schwarzenegger flanked by a number of bikini clad women. Applicants were invited to caption the photo and submit their CV for an “editorial assistant” position at a “central London magazine company.” Later, I was told that if they’d put the company name, no one would have applied. Apparently, my caption was funny enough to secure me an interview.

Would I have applied had I known? Probably. I was desperate. And as far as pornography went, I was an innocent—as we all were back then. This was the pre-internet age when porn meant ripped-up magazine pages found in the woods. There was no Pornhub. Can you imagine? My own daughter, now around the age I was when I took this job, has likely already seen more explicit material than I even knew existed.

This is how it worked: A porn shoot—usually in America—would start with softcore nudity and progress to hardcore sex. Photos from different stages were sold to various publications, tailored to their audiences and regulatory constraints. Mayfair and Club took the early shots; Danish magazines took the hardcore ones. Razzle did a lot of its own shoots as its uniquely British, Carry-On style of ordinary girls frolicking in baked beans was not really catered for in Los Angeles.

The photo sets Paul Raymond bought would arrive in the office, and my job was to construct a story to accompany them. If the model was new, I’d invent a name and personality for her. Lonely and uneasy in my peculiar job, I amused myself by naming models after my friends and giving them scenarios my friends would recognize. If a model proved popular with readers, she’d appear in future issues, and a fictional relationship was born between anonymous writer and anonymous model.

Which brings us to “Ginny.” Ginny, named by the staff, first appeared in Club as a gorgeous, wholesome-looking blonde. I gave her a perky personality and a delight in showing off her body. Over six months, she became thinner, paler, and, finally, unusable. “Probably drugs,” the editor said. “She’s not perky anymore.” And that was it. Ginny was discarded. Remember, we only saw the first section of photos; there were thousands more. Denmark’s gangbanged ‘Ginny’ was probably as dissociated as Lily Phillips. As the months progressed we just saw the collateral damage.

While all this was happening, I lived with my estranged father, whom I’d met only a few years earlier. He was my sole contact in London. This is relevant to the discussion about Lily Phillips that has erupted over X in the past weeks. My then 45-year-old father delighted in discussing my job with me, his 20-year-old daughter. One day, to my numb shock, he brought out his pornography collection. It wasn’t Club or Mayfair but the ultimate low-grade freak show, printed on paper so flimsy it nearly ripped.

Mortified, I didn’t know how to react. What could I have said? I had nowhere else to go. My father charged me almost all my salary to live with him and, in a weird Dickensian twist, watched me do housework for his amusement. So after a day of immersion in pornography I came home to a father who thought my job at Paul Raymond gave him permission to dismantle all normal boundaries between us. There was no notion in his mind that there were limits of his own that he should impose My being his daughter didn’t matter. Looking back, I’m furious. But at the time, how does one comprehend such malevolence while living inside it?

It wasn’t just him. Every man I met liked hearing about my job and couldn’t fathom that I wasn’t a porn enthusiast. Even “nice” men wanted details about the letters and confessions I wrote. My job flipped a switch in them, as if I’d signed a proclamation of nymphomania. This dynamic, taken to extremes, is what I see in the discourse surrounding Lily Phillips. To men, her participation in pornography equals consent to everything—and they impose no limits on themselves. This dynamic leads inexorably towards evil.

Pornography is built on a lie of existential proportions: the lie of female sexual response. At my interview, when my young, personable, left-leaning boss asked my thoughts on the magazine, I suggested it might be interesting to create a women-focused version. He laughed. “That’s not what this job is.” Pornography exists for one purpose: to give men orgasms. Men must never be confronted with that lie. My entire working day was spent perpetuating it, and I was astonished that no one seemed to consider for a moment that it was a lie. Lying on that scale is gruelling. After two years, I would’ve received a massive pay rise, as this is the point where those who can sustain it have made their compact and earned their rewards.

After two years of training in pornography a would-be journalist was rendered an asset to any mainstream organisation, so needed to be bribed to stay. The discipline required in pornography magazine production made its alumni desirable everywhere. On my first day, I was told that missing a deadline meant instant dismissal. I never missed one, though the deadlines were relentless. And the writing? A writer capable of producing, again and again, exactly 1,000 words of clean, compelling copy, with at least two payoffs that elicit an orgasm in the reader, will excel in any field of writing they choose. Pornography was both the most professional and the most degrading writing school imaginable.

Like Ginny, I lasted six months. Unlike Ginny, I quit. Intuitively, I knew that if I stayed I would see too much and collude too far to have a normal life. My boss said he knew I’d go as soon as I was any good. He also gave me the odd praise that I was ‘the only one who didn’t cry.’ Perhaps it’s an strange thing to be thankful for, but I’m glad to discover I remain shockable, as I was this week by Lily Phillips’ dissociated expression, eerily reminiscent of Ginny’s. And shocked anew by the callous evasion and condemnation of Phillips by prominent men on X.

I left my father and the industry behind, buying a one-way ticket to Hungary, where I lived for two years, insulated by a ferocious language barrier. I’d glimpsed an existential evil. Lily Phillips remains immersed in it, sinking deeper in a world of pornography far more extreme than anything we imagined back then. Worst of all, going by what has played out online over the last week, men don’t care. There is no limit to their indifference. Think on that. No limit.

Thank you for reading this Letter From A Poet.

Please support my work with a paid or gift subscription.

Currently there’s 20% off a year.

Catch up with all Letters from A Poet here:

Share this post