Dear Reader

Ten days from now, on June 12th, my novel Ocean will be in the world. As I move toward publication — a moment I’ve worked toward for six years — I find myself reflecting not only on the joy of that achievement, but on the long, strange cultural backdrop against which this book was written.

This week, two significant events landed in the UK literary world: Ursula Doyle’s legal settlement with Big 5 publisher Hachette, and JK Rowling’s announcement of a legal fund to support those discriminated against for their gender-critical views. For those of us who have lived through the past half-decade as gender-critical authors, these moments feel like a turn — a sign that, at last, some of what we endured is being recognised not just as bad behaviour, but as unlawful discrimination.

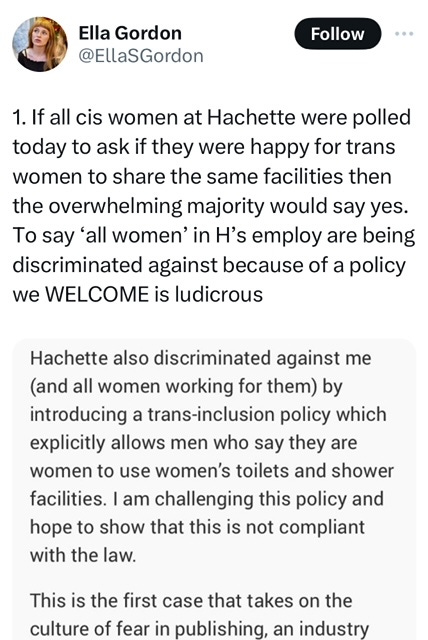

But before we let the past fade (and how tempting it is to forget — like the horrors of lockdown, or any other collective convulsion), here are some screenshots from just over a year ago, when Ursula started her crowdfunder for her tribunal case: tweets from an Editorial Director at a Hachette imprint.

Looking at these now, they are shocking, especially coming from a senior executive in a massive company. But even just a year ago, in the captured bubble of publishing, they were seen as perfectly acceptable. They were never deleted.

Since the Supreme Court ruling, the tone on social media has cooled, at least on the surface. But public silence doesn’t mean private feelings have changed.

When I was still an author at Hachette, Ursula Doyle was a publisher there. We didn’t know each other then, but we both experienced things that, looking back, were astonishing — and reflective of the atmosphere that shaped her legal case.

In 2021, Hachette sent out a questionnaire to its authors, demanding intrusive personal information about gender identity, family background, even where your parents had gone to school — data they had no right to collect from non-employees. Though it was presented as “voluntary,” it didn’t feel that way when it arrived personally from my publishing team and was followed up with reminders. There was no box to tick for “I don’t believe in gender identity.” There was no way to decline without conflict — and conflict is what the rights-impoverished author rightly fears.

I protested and was grudgingly removed from the list. But from that moment, I knew my card was marked. Ursula, I later learned, refused to pass the questionnaire to her own authors — a quiet act of integrity that, I am sure, marked hers too.

Around the same time, a “TERF blocklist” began circulating on Twitter, compiled by a group calling themselves the “Young Refuseniks.” After it was pointed out that blacklists are illegal in the UK, the group disbanded — or more likely, slipped underground. But not before a list of “TERFs in publishing” was widely shared, with people inside my own publishing house liking and retweeting it. I wasn’t named then, because I was still anonymous online. But many of my friends were. Ursula was.

I raised concerns: how could I trust that my book would be fairly supported by people who saw women like me as contemptible? Who were content to try to destroy the reputations of fellow professionals in plain sight? I don’t know what was said behind closed doors, but I do know that trust evaporated. Eventually, I left, taking my novel with me.

A year later, I had signed with Eye Books, my new publisher, and was working to bring Ocean to completion. I had also dropped my anonymity on Twitter, feeling exhausted by the weight of inauthenticity. That choice proved more consequential than I could have imagined: within 24 hours, my ‘outing’ post had 650,000 views, and I was swept into a tidal wave of welcome and outrage in equal measure.

In the middle of that storm, I was invited to chair an event at the Edinburgh Book Festival. I accepted gladly. Then, without warning, I was told I was being “moved” to a different event.

I asked why.

For six months, I was stonewalled. Friends urged me to let it go, to accept the change and move on. The attempts to dissuade me intensified. I was told I was ‘extreme’ for wanting to know what had happened; that I was being unreasonable for protesting about something ‘normal’. But if there was nothing to hide, why would no one explain?

With help from the Free Speech Union, I filed Subject Access Requests.

Eventually, the truth emerged: an email from an individual at a Hachette imprint had requested my removal because I was “a vocal opponent of trans rights” and would make the authors I was booked to chair “uncomfortable”.

It was false. It was defamatory. It was devastating.

In the end, the Book Festival were the ones who gave me the incriminating email. Like other festivals, they want an end to the tyranny of activists, who jubilantly lay waste to entire cultural institutions: or, as in the case of the Baillie Gifford debacle of last year, destroy an entire funding stream for all the nations festivals.

The cost of uncovering what I knew to be true was high: friendships strained or lost, trust eroded, months of personal anguish. On top of the previous losses, it felt hard to imagine how to continue. Fortunately my friends, battered, scarred themselves, and also the most resilient people I have ever known, gave me courage. I chaired the two alternative events offered to me, one with Samantha Harvey, whose book Orbital, went on to win The Booker Prize. I wrote about it here.

I was, and am deeply grateful for the opportunity that I was given. But I can feel this, at the same time as the certainty that I should never have been subjected to what happened to me. One does not cancel out the other. As my heroine, Helen, discovers in Ocean, paradox lies at the heart of most painful human experience.

Now, a year on, I see how the landscape has changed. Neither the blacklist, nor the intrusive questionnaire, nor the defamatory email could easily happen today, at least not in the open. The law has clarified; institutions now understand their responsibilities clearly.

But here’s the thing: when the public channels close, where does the hostility go?

Prejudice doesn’t vanish when the expression of it is no longer fashionable.

A small but vivid example unfolded this week.

At Hardwick Hall, a public artwork called A Virtuous Woman invited visitors to stitch onto the dress of a statue the name of a woman they admired. Someone stitched “JK Rowling.” Later, someone else stitched over her name to cross it out, using the pink and blue of the trans flag.

The National Trust, which displayed the piece, did nothing to address this defacement. So feminist activist Jean Hatchet travelled to Hardwick Hall and unpicked the stitched-over vandalism herself. She was not challenged. And though the Trust expressed “deep disappointment,” they have not called for the defacement to be restored.

Read the whole fascinating piece here.

What this small episode reveals is not just a shift in policy, but a shift in public confidence. A year ago, the person doing the stitching-over would have been certain they were in the cultural right. Today, they act furtively. Activist backlash comes quietly, not triumphantly. Additionally, a year ago it is highly unlikely Jean Hachet’s repair action would have gone unchallenged or unpunished.

But prejudice gone underground can make it harder to track, harder to name.

And that’s where the deeper tension lies.

Some amazing books have come out of this struggle, all (apart from Simon Edge’s brilliantly satirical novel In the Beginning) non fiction. Graham Linehan’s Tough Crowd is a harrowing account of his cancellation. Victoria Smith’s analytical works, Hags and Unkind are stunning feminist responses to this new age of misogyny.

Meanwhile I was fighting for the space to write my kind of novel that was not directly about ‘the times’ — to hold onto the freedom of my own kind of fiction, of creativity, of metaphor, the very tools that were most under threat.

Ocean is a book about a woman remaking herself, surviving, reclaiming meaning. And while I was writing it, I was waging a parallel fight: for the right to name myself, to preserve the meaning of woman, to resist the erasure language itself. Ocean is a novel made out of the struggle of that time. It was written while these things were happening in real time — at my publisher, among my friends and family, in almost every previously trusted media outlet.

I feared, often, that I would lose my ability to write at all. As former friends turned away and creative support ebbed I wondered how I could carry on, and what the future was for this story that felt hewn of of madness.

But I carried on. Writing, in the end, is how I function. In the face of pressure, fear, isolation, I write

Now, two weeks before publication, I stand in a place I could hardly have imagined seven years ago, when I first sat at my kitchen table and opened the pseudonymous Jean Rhys Twitter account, thinking: I have to do something in the face of this madness.

I cannot know what hidden judgments may still shape the reception of my work. None of us can. Creative life has always been uncertain, shaped by unseen hands and unspoken decisions. But here’s what I do know:

I have survived. I have made something — not a reaction, but a novel. A hard-won act of imagination, forged in the teeth of cultural storms, written through fear, abject loneliness, and doubt.

Ocean is not just a book about a woman remaking herself; it is a book I remade myself to write. It carries the imprint of these mad years — their pressure, their losses, their beautiful moments of defiance — but it also carries the proof that art can transcend the times that seek to strangle it.

Thank you for reading,

Until next time,

Polly xx

You can out more about Ocean here, and you can preorder Ocean from Amazon here. I hope that you will, and that you will love it.