The World Does Not Negotiate

Shackleton, Shylock and the feeling of freeze

Hello, I’m Polly Clark, novelist and TS Eliot Prize–shortlisted poet. Monday Night Reads brings thoughtful writing direct to your inbox every Monday at 7pm. Recent highlights include my interview with Graham Linehan and my essay Reality, Delayed about being stranded in a hotel listening to Helen Webberley.

If you value my work here, please consider a paid subscription or buying me a coffee. Your support makes all the difference and keeps this space alive. My latest novel Ocean is out now. My poetry retrospective, Afterlife: New and Selected Poems is published February 26th 2026.

Dear Reader,

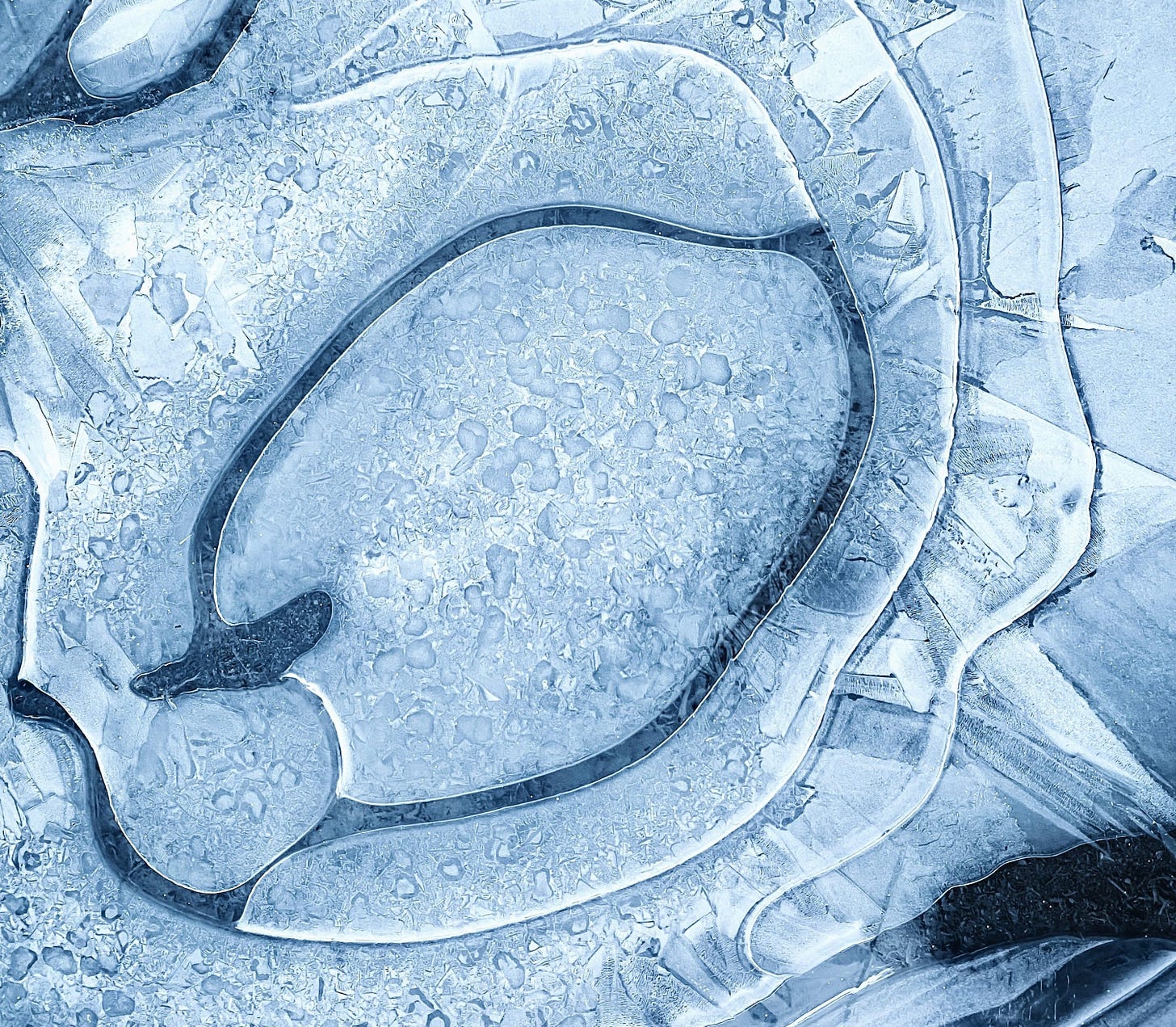

As I write, London is entering (in lovely British understatement) a ‘cold snap’ which sees temperatures plummet to the point where the marina freezes. This is not Instagram aesthetics. This is physics bursting into your bedroom. I was jolted awake by the explosive crack of the ice against the hull, and leapt out of bed with the fervent instinct that surely possessed Shackleton as he rushed to survey the damage to Endurance. Encroaching ice can crush a hull: the force of a solidifying body of water is immense. Thankfully, this is Surrey Quays, not the Weddell Sea in Antarctica where Endurance finally sank in 1915 — but still, it’s a concern.

The Good Ship Sanity is made of fibreglass (the posh seafaring term for plastic), unlike Shackleton’s heartbreakingly majestic wooden ship, and can withstand most onslaughts. The terrible sound was mainly reverberation through the bilges. She would live to bob another day, a metre from land. A plastic boat resists most things, including decay, making abandoned boats an environmental disaster, but also prolonging their lives as safe residences. The older I get, the less interested I am in moral absolutes that refuse contact with the physical world.

Back to the big freeze. Wall People — those whose walls are straight, dependable, and happy to take a picture hook — need not have the cold snap intrude upon their awareness until they glance out of the window. They can admire the external world’s frozen coruscations from the comfort of a clear inside.

But the wonder and the hardship of boat life is that no elemental experience is really separate. My boat is insulated with gym flooring on every available surface; I have what’s known as a ‘rug buddy’ under my carpet to take the edge off the freeze when I take that first step out of bed; my heated throw is on all the time, as are my infrared panels. I’m not sure how this latter heat works exactly, and am mildly concerned I’m being microwaved, but the point is it does work, and it’s a lovely heat. I imagine it as frog-heat: a permanently preserved moment before the frog realises it’s too late. My cabin is sealed, so there comes a point in the night when the panel needs to be switched off, as it’s getting fetid rather than warm. The result of this is that I wake to a sensation of my head in a snowdrift while my body is in a sauna.

I made the journey to the galley for coffee, through my saloon where a larger rug buddy warmed the first two centimetres above the floor (urging me to squidge my toes into the wool, as if into sand on a sunny beach), and the air whispered inside the bubble wrap I have taped to my aged windows as a temporary/indefinite insulating measure. My mug was so cold that I had about three minutes to drink the coffee before it went cold too — but I was surrounded by peace and darkness. I got the rest of the heating on and went back to bed, to be greeted by an email from the marina office alerting us to the freeze and advising we fill our water tanks, as it was likely the pontoon pipes would freeze. Fortunately, I was all stocked up water-wise. I had no reason to go outside for some time.

This time is more precious to me than I can describe. It is not just solitude; it is dreaming. I crave its simplicity and its peace. In fact, I think you can only get peace like this if you are willing to go head to head with the elements, to accept the physical reality of life. Cold seems to be closely tied to silence, somehow; and to space. From my porthole I peeped out over frosty pontoons, the sun a pristine gold; the shade a white-edged silver. A little later, while a casserole ticked away in the slow cooker, I got on with the vital tasks that, for me, can only be completed in this environment. Reading. Thinking. Writing.

The book I have decided to read — which cannot be read if one is bustling about in normal temperatures — is The Count of Monte Cristo. I expected it to be escapism, with probably a huge weight of historical detail to process, but it is instead a starkly relevant and unputdownable romp through revenge and petty grievance inside the irresistible machinations of history.

I’m barely ten per cent through this mega doorstop of a book, but already everyone is behaving just as they do now. The innocent Dantès is imprisoned after being framed for Bonapartism; the deputy magistrate, Villefort, who has incarcerated him, is a low-rent Pontius Pilate type who, realising he is innocent, would have freed him — until he found out his own father, also a Bonapartist, would be implicated if he did. When the Restoration fails and Napoleon is back in power, Dantès’s friends petition the official. In a lovely moment revealing the farcical nature of much political decision-making, the political reversal means Dantès is innocent now, even if he were guilty before. But Villefort is certain Napoleon’s return will not last, and so, with a big display of enthusiasm for releasing him, simply delays. As he predicted, Napoleon’s return lasts only 100 days. Dantès is de facto guilty again, and Villefort off the hook.

Pure politics. Delay masquerading as prudence; enthusiasm that costs nothing; virtue postponed until it is safe. Readers of this Substack will see the parallels to our current moment perfectly.

This brings to mind a recent fascinating article in The Atlantic, which the X algorithm brought my way this week. In ‘What If Our Ancestors Didn’t Feel Anything Like We Do’ Rob Boddice argues that we simply cannot know what people in another time felt about anything — that they are unrecognisable to us, and that there is no commonality of feeling between human beings across time. The lie is given to that thesis immediately by my seeing my own time and place in the feelings and actions of characters in literature from the past. But it is, as the article’s author, Gal Beckerman, states, an interesting take worthy of attention — if not in the way Boddice intended. On the surface, at least, it invites consideration of people in the past as individuals, not the great lumpen mass we think of as ‘historical people’.

The problem with Rob Boddice’s argument is not that it is wrong, but that it is incomplete in a way that flatters power. What it flatters, specifically, is class. Abstraction is not neutral. The ability to deny common feeling, to treat experience as radically unknowable, is far easier if your own body has rarely been at stake. If your accent, your housing, your safety, your credibility have never depended on being recognisable to others, then difference can remain an intellectual position rather than a lived risk.

Boddice distrusts empathy (he wants a T-shirt printed with ‘Down with empathy’) — a bold path for a historian to take. Unpicking his argument, we reveal the nihilism that is our age’s great malady. The problem is this: if we cannot know what another person felt, we have no responsibility to care. What he is essentially arguing for is the intersectionalising of human emotions in so many ways that common human feeling is, in effect, obliterated.

It is illuminating and historically vital to incorporate context into any analysis of how someone might feel or have felt in a given situation; but when context overwhelms the subject, understanding is lost, not gained. In our own time intersectionality is used as a weapon to shut down whole areas of human experience, when it could be used to understand them better. My experience as a woman is valid in its own right. It can be better understood if we take account of my time period and class origins, as these may have influenced or exacerbated that experience, or shaped my ability to articulate it — just as my race, or whether or not I am disabled, may also shed light on it.

Done in good faith, none of these intersections distorts the essential experience, turns it into a different experience, or reduces it. Applied in bad faith, as it often is by those with a nihilistic bent, my experience is simply assimilated into the dominant experience. If we are not vigilant, intersectionality becomes a tool of the powerful to devour and repurpose the experiences of the less powerful. This is the logical end point of abstraction when empathy is treated as a weakness rather than a faculty.

It is fascinating to discover that Boddice was born in a northern town of no particular distinction and prided himself on shedding his accent. I was brought up in the north and similarly shot those knobbly consonants into outer space when I found myself in the verdant grasslands of the middle-class south. It wasn’t snobbery; it was survival. (I also did this when I moved from my northern town to Scotland — an English accent of any stripe was a death sentence for a twelve-year-old in the rural Borders.) I have met others who have done the same. A talented and well-spoken leader of a sales team at my former publisher was from Oldham, like one side of my family. This confession was literally whispered. ‘What did you do with the accent?’ I asked, in awe. He looked at me as if I were mad. ‘Killed it, of course. Do you think I’d have the job I do with an Oldham accent?’

Accent is a record of shared physical experience; to erase it is to buy safety at the cost of legibility. That trade-off is rarely neutral. To move into abstraction — to insist that experience is unknowable, unshareable, beyond recognition — is far easier if your own bodily self is not read by others as risky.

In Boddice’s case, that move is made possible by the careful removal of anything that might interrupt a claim to neutrality. A person still marked by accent or social shame would struggle to make this argument function as disinterested knowledge rather than self-protection. And in this, something else is revealed: we do, in fact, understand how others think and feel — and often it is precisely that understanding we are trying to escape. I know this because I, and so many others, have made the same move myself. I learned to sand down my own visibility, and I know the cost of doing so. Abstraction pretends there is no cost; lived experience knows otherwise.

This is precisely the manoeuvre that Shakespeare refuses. In The Merchant of Venice, Shylock makes his plea not on the basis of shared culture or belief, but shared embodiment. “If you prick us, do we not bleed?” he asks — not sentimentally, but logically. Difference does not abolish recognisable vulnerability. We ignore this, and the entire sweep of literature that insists upon it, at our peril.

Outside, the ice presses again against the hull. It does not ask whether I am eighteenth-century or twenty-first, northern or southern, housed or afloat. It exerts force; I respond. That exchange — pressure and recognition — is the material grounding of shared experience. Alone in the freeze, I am in better company than those who refuse to imagine anyone but themselves.

Thank you for reading

Polly x

If you have enjoyed this essay or found it thought provoking, do please consider supporting my work with a paid subscription or a cup of coffee. I appreciate every one.

Writing with company

Hour Club is a small group that meets on Zoom every Monday at 7pm. We’ve been meeting for around eighteen months now, and in that time books have taken shape, drafts have been finished, and confidence has grown.

The principle is simple: books only get written if words are put down on the page, and that is much easier to do in the right company. Hour Club isn’t about instruction or critique. It’s about showing up, writing, and being accompanied by others who are taking the work seriously.

You write your own book. But in Hour Club we encourage, understand, and gently hold one another to account — and we share each other’s progress, whether it feels large or small.

You can read more about Hour Club here, and about me here. Depending on interest, I may open an additional group, but I’m keen to keep each one small.