Hello! If you are new here, do check out Letters From a Poet, each of which comes with a specially recorded poem and Letter.

Paid subscribers can access my Writer Interviews with Graham Linehan, Jenny Lindsay, Gillian Philip, and the complete serialisation of my debut novel Larchfield. There is a 20% discount off an annual subscription to tempt you. I need your support, and am grateful for every one of you.

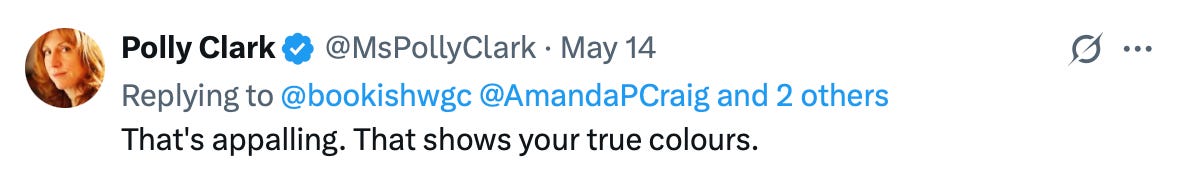

I first set up Monday Night Reads to serialise Ocean my new novel. That novel is now published June 12th! It will MASSIVELY help the book you made possible if you pre-order the hardback, or buy the Kindle and review! If you post a photo of yourself with the book I will repost! Let’s get everyone reading Ocean!

You can also Buy Me A Coffee — I consume lot of coffee writing these posts.

Thank you for being here. I treasure every one of you, free or paid.

Polly x

Dear Reader

Were you ever a fan of BBC Radio 4’s Woman’s Hour? My younger, pre-motherhood self balked at the notion of a ‘special’ programme for the ladies, suspecting it was meant as a silo for silly things. But as I got older and accumulated more ‘lived experience’ as a woman, I began to find it more interesting. Perhaps I was becoming its target audience.

Though never Women’s Institute-level anti-feminist, the show always seemed to skirt anything too politically uncomfortable. In retrospect, it’s as if the trajectory of Woman’s Hour has mirrored the growing problematisation of ‘womanhood’ itself over the last decade.

As happened with Mumsnet, the intensification of gender ideology gave this cosy 10 a.m. coffee-stop unexpected relevance. But Woman’s Hour took the opposite approach to Mumsnet, whose forums became hotbeds of political resistance and rare ports of sanity for women. The once-loved programme instead silenced dissenting voices, and a full-throttle gender takeover began — centring trans-identifying men and erasing the term ‘biological sex’ except as something to be ‘contested’. I haven’t listened to Woman’s Hour since Jenni Murray was squeezed out as presenter and gender activism took hold across the BBC.

But last week came exhilarating news: Helen Joyce had at last been invited onto the show to discuss the Supreme Court’s ruling on the definition of sex. Women everywhere dropped everything to tune in — probably, like me, for the first time in years. I expect the listening figures were through the roof.

🎧 Listen: Helen Joyce on Woman’s Hour (this is the interview that set the internet alight — and the one I’m writing about below).

I had heard Helen Joyce speak before — though not on the BBC, who have simply pretended the most erudite speaker we have on this subject, and Director of Advocacy at the human rights charity Sex Matters, doesn’t exist. Most recently was earlier this year at the Sheldonian Theatre in Oxford in conversation with Julie Bindel for the Oxford Literary Festival. But this broadcast was different. This was after the Supreme Court judgment, and something in Joyce’s voice had changed. Or perhaps it was that the context had changed. The law had caught up with common sense. Joyce was no longer making a moral argument; she was stating a legal fact.

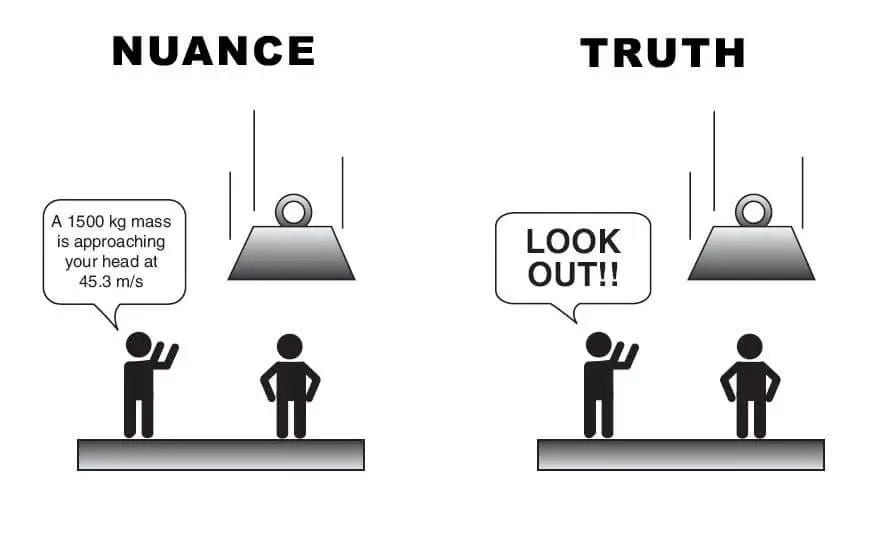

And what was so electrifying, so strangely unfamiliar, was this: she did not offer nuance.

She didn’t say “it’s complicated.” She didn’t soften her position for the feelings of others. She didn’t offer exceptions. She didn’t even apologise for not doing so. She simply said: women are female. Men are not women. Women’s spaces are for women. And that is the law.

The interviewer, Nuala McGovern, was wrong-footed. You could feel her scrambling for the familiar moral terrain. What about those who are hurt by what you say? What about those who feel excluded? Joyce wouldn’t bite. She didn’t care to defend a position that no longer needed defending. Her role was not to sympathise, but to state. And her certainty came not only from intellect, but from the astonishing novelty of having the law at her back.

This moment laid bare something that has haunted the women’s movement for years: the tyranny of nuance.

Let’s pause here. What is nuance? Etymologically, it comes from the Latin nubes — cloud. A thing made misty, softened around the edges. In literature or music, nuance can be a richness. But in law? In boundaries? It is obfuscation. It is evasion. It is a way of not saying no.

No one suggests a nuanced approach to burglary, or the age of consent. The law is, by design, a set of boundaries. It is there precisely because emotion, ambiguity, and personal belief must yield to fairness and clarity. Only in the area of women’s boundaries is nuance insistently demanded. We can see it in the prosecution of rape cases, where the parsing of ‘consent’ effectively destroys the victim’s case (and character). And now with the advent of gender activism it has spread to our spaces, our rights, our sports. We must be kind. We must be willing to make room. And always, we are pressed to explain why we won’t.

Nuance is not evenly distributed. Men do not apply it to themselves. When men assert a right, or an opinion, they are not asked to be more nuanced. They are respected for their clarity. Yet when women speak clearly about our own boundaries we are considered cold, cruel, or radical. We are told our stance is not “helpful to the debate.” That there still is a debate. That our no cannot be final.

Joyce’s plain speaking reminded me of another woman, some years ago now, who also refused to nuance the truth. Germaine Greer, in a now famous television interview, was asked whether she cared about offending men who said they felt "trapped in the wrong body." Her answer: “I don’t care.” And she didn’t. Not because she was cruel, but because cruelty was assumed in the question. She refused the emotional script being handed to her — the one where women must always be kind, always be understanding, always make room — at the expense of themselves and of the truth.

The brilliant Germaine Greer was having none of it — but she didn’t have the Supreme Court ruling to back her up which makes her clarity all the more admirable.

Nuance was the banner under which women’s rights were rapidly dismantled in plain sight. Don’t be absolute. Don’t be exclusionary. What about the vulnerable man who means no harm? What about the one who’s had surgery? What about feelings?

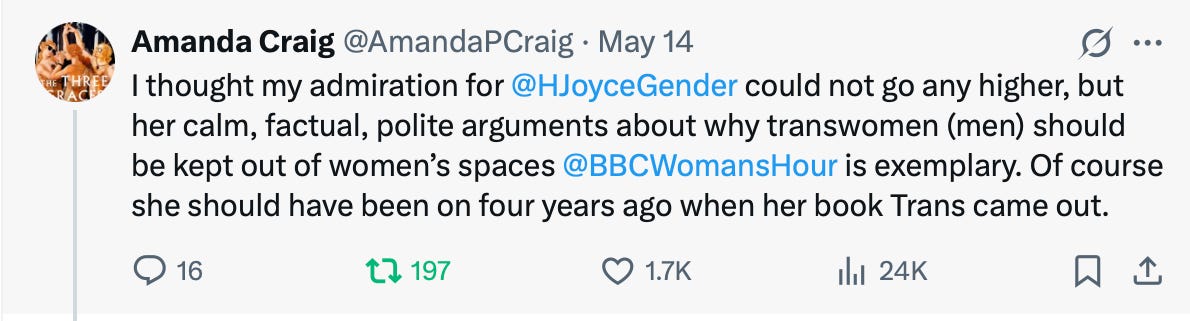

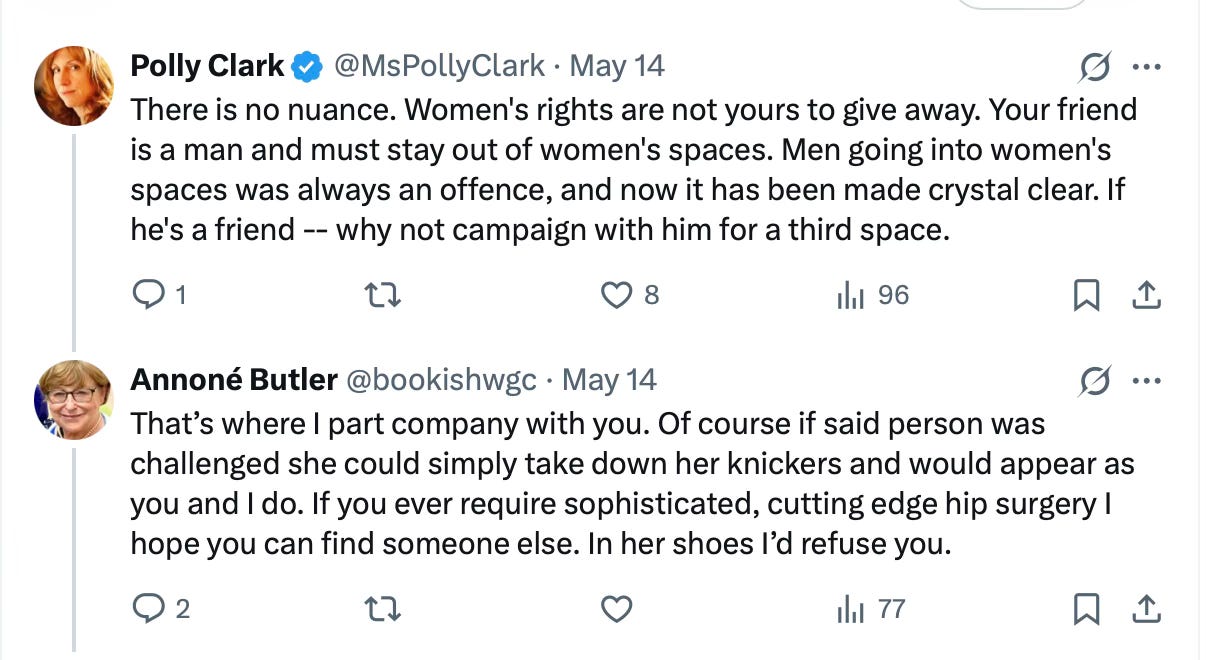

And it’s still happening. In the jubilant atmosphere after Joyce’s appearance, I had an exchange on X underneath this post by Amanda Craig:

The Supreme Court has reaffirmed that sex matters in law, and that single-sex spaces can be just that. No more soft-focus blur. No more emotional coercion disguised as compassion. The court did what so few have dared to do: it told the truth in plain language.

And so did Helen Joyce.

We forget how recently this clarity was missing. Under the Scottish Government’s proposed Gender Recognition Reform Bill, a person could self-declare a new legal sex with no medical transition, no diagnosis, and no waiting period. This placed it in direct conflict with the Equality Act, which protects single-sex provisions. The UK Government blocked the bill on precisely those grounds. But for years, public bodies, charities, and institutions have already been acting as if self-ID were law — as if the question were settled, and women who objected were merely being difficult.

That fog — that dangerous, legally unsupported ‘nuance’ — has now lifted.

And yet, Woman’s Hour aired Helen Joyce’s interview between two others that perfectly captured the nuance double standard. Before her came Robin Moira White, a trans-identifying male barrister and activist, who claimed that the Supreme Court’s ruling violated the European Convention on Human Rights and would likely fail in Strasbourg. He was not interrupted. He was not corrected. When these points were put to Joyce in her interview, McGovern asked irritably, “Why are you smirking, Helen?” “I’m not smirking, I’m smiling,” Joyce replied calmly. She was smiling because White’s bluster is just that. The ECHR will not ‘overturn’ the ruling. But McGovern had made a serious attempt to portray Joyce as sneering, rather than challenging White on his misinformation.

After Joyce came Sacha Deshmukh, a representative from Amnesty International UK. He falsely claimed that the judgment was only 33 pages long (it is 88), and protested that the ruling could lead to trans identifying males being excluded from rape crisis centres as if this was some kind of newly minted regulation. Single-sex exemptions in such services have always been legal under the Equality Act, in order to ensure a female only provision for vulnerable women. The judgement simply reaffirmed that it it is perfectly legal to exclude males, however they identify, from single-sex services. There was no challenge to Deshmukh on either his facts or his logic. No request for nuance. No questioning of whether his view — that males should be allowed in these spaces — might be hurtful, or misleading. Or plain wrong.

Helen Joyce, on the other hand, was pressed. Persistently. Despite being right. Despite speaking not just for herself, but in defence of settled law. It was as though the BBC — and the host — simply could not accept that there was no more debate to be had. That a woman could say no, just because she could. That such a thing might not require apology.

It put me in mind of the many systems of justice where a woman’s word is worth half that of a man’s. That is the cognitive dissonance of hearing Joyce pressed like this on Woman’s Hour. A woman, laying out a truth enshrined by the highest court in the land, is nonetheless expected to defer, to explain, to soften. And a female interviewer struggles to side with her.

Why do women find it so hard to side with women? What is it in us that still flinches at our own authority?

Joyce spoke like a citizen. Like someone who knows her rights, and yours too. The clarity of it fed me. It felt like something I hadn’t known I was starving for.

We are not used to hearing women speak like this. And that, I think, is the point.

We should be.

Thank you for reading.

Until next time

Polly x

In the run up publication of Ocean, I’m having a lot of fun creating these signs to evoke some of the emotional undercurrents in the novel. Some are of me, and also of others who have a connection to the book or the setting. Follow me on Instagram (@MsPollyClark) to see them all as they appear. Thank you to my daughter Lucy Forrester for her brilliant modelling of ‘Sometimes I just don’t like you.’

I first set up Monday Night Reads to serialise Ocean. That novel is now published June 12th! You made this book possible — and there’s still more you can do! It will MASSIVELY help me and the book if you pre-order the hardback, or buy the Kindle and review! If you post a photo of yourself with the book on social media I will repost! Let’s get everyone reading Ocean — the book that Substack built!