Dear Reader,

Almost every man I have ever known was troubled by my ability to make him laugh. Here’s what they did: interrupted to say, "I think those people over there can hear"; redirected the conversation; pointed out the window at something irrelevant and restarted the conversation with their own anecdote; laughed, then looked embarrassed, as if they’d accidentally said they loved me or shown their pants; left the room on an urgent errand. In my experience, men don’t like laughing at women’s jokes. They want women to be the joke. If you can be the joke, you can get a man to laugh uproariously. Maybe it’s like being incredibly good in bed: a man can’t just enjoy that. It makes him jealous and suspicious — how many men have you practised on?

So I’ve felt all my life that any irreverent take on the world I have is something to be ashamed of. Exuberance makes me unattractive to men. I’ve never really had anyone to be funny with, until my work. In my writing, where I please myself, I can be as ironic, ludicrous, and exuberant as I like. I can be myself — and I am.

Over time, I’ve discovered that if the humour and the joy are in the work, one step removed, men will laugh. You don’t get to see them do it, but they’ll tell you it’s funny afterwards. They may ask, surprised: “Do you mean it to be funny?” or, “How did you write this?” They laugh — just not in front of you.

Still, it’s a lonely existence. One that never relaxes into a joyful embracing of all life’s facets — its sadness, its terror, its absurdity. I’ve spent decades only being myself in my work. I’ve longed to find that connection with people in life that writing gives me in private. This is the power of the writing partner — someone who sees you and gets you. It’s as rare as the perfect romantic partner.

I had a collaborator like that once. No need to go into it; it’s over now. (Short version: creative liberation — unimaginable pain — great work — the end.) But in those years, I could say anything in the work and he got it. The more outlandish, the more secret, the more he drew it out. He never tired of it. In the work, he brought out my exuberance and gave it witness, welcoming it like no one had in the real world. In all other respects, he treated me with complete contempt. The price of being seen was high. But in this one regard, my true spirit flourished.

That’s how I found myself laughing as I wrote Ocean, even as my heroine endured emotional devastation that mirrored my own. Art is energy: even sadness, in art, is animated by energy — and energy is a kind of joy. I don’t mean ‘joy’ in that dreadful tone-of-voice way, but writing as a life-force. That force is always exuberant.

In real life, for a woman to show happiness about her own existence is often a no-no. We’re supposed to be toiling for others, not delightedly not giving a shit. We’re meant to be the foil for others’ happiness — not simply happy. But in my story I gave full rein to everything energetic in my nature, and this person — let’s call him Ming— could take it all. On the page I was liberated from the shame of my joyfulness.

When I made the mistake of letting that joy spill into real life, Ming shut it down without mercy. It was a kind of scorched-earth mentoring. SAVE IT ALL FOR THE WORK, I suppose he was saying — but isn’t it normal to be joyful outside of work? Well, no. Not for me. Maybe this is why so many writers drink or take drugs. It’s an impossible split: if the person in the work is loved, why is the person who wrote it no more than a malfunctioning prop? The division of self — the loved imagined version and the shameful real one — can be almost unbearable.

It wasn’t until I found myself inside the new-wave women’s movement resisting gender ideology that I discovered a shared kind of exuberance and humour. Women are funny, and we laugh at each other’s jokes without feeling diminished. Even in the darkest days, I’ve laughed out loud at the way so many of us have written about it. Kathleen Stock, since her cancellation, has become one of the funniest columnists around (knocking the regime handmaidens we were supposed to find funny, like Caitlin Moran, into a cocked hat). Julie Burchill has always been funny but seems to have found a whole new gear with the material gender ideology provides. On social media, female wit crackles: Helen Dale, Jane Harris, Julie Bindel never post a dull tweet.

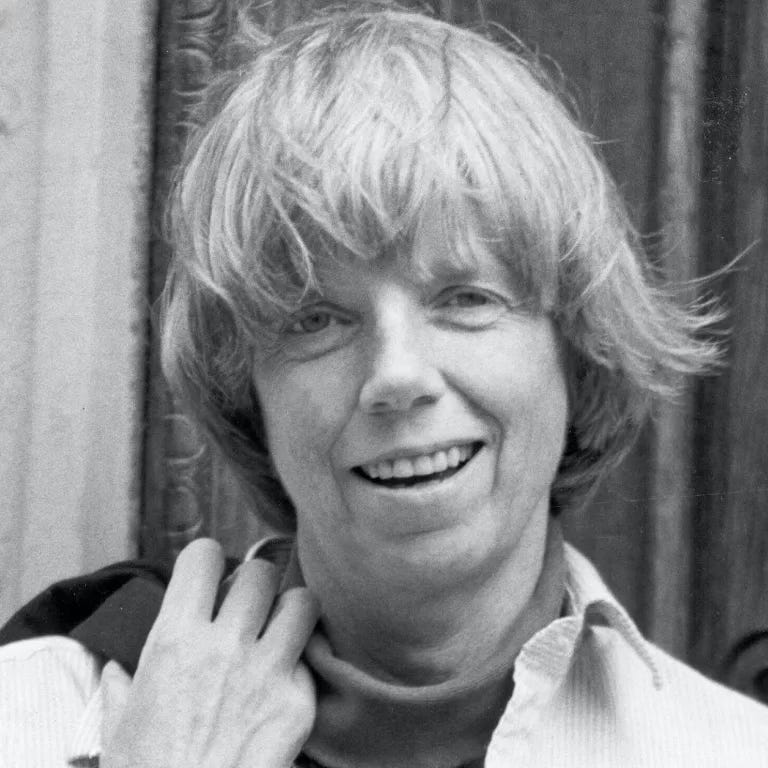

Towering above them all is JK Rowling — female exuberance incarnate. Unapologetically triumphant after the historic win by For Women Scotland at the Supreme Court this week, she posted the photo of the ages:

In these women, I see the truth: it wasn’t that I was always wrong, terminally unfunny, a fleshly embarrassment. It was a woman-hating world that can’t tolerate the challenge to authority that autonomous female joy presents. We’ve lived through it. We survived. And more — we triumphed.

I’ve been reading Julie Bindel’s Lesbians: Where Are We Now, which is an object lesson in female joyfulness. She describes the infamous Town Hall debate of 1971 in New York, captured in the documentary Town Bloody Hall (1979), directed by D. A. Pennebaker and Chris Hegedus. The panel featured Norman Mailer and feminist luminaries Germaine Greer, Diana Trilling, Jacqueline Ceballos, and Jill Johnston. The debate, ostensibly on women’s liberation, became a battleground of egos.

Greer, brilliant and beautiful, engaged Mailer with charm and sharpness — playing on desire, managing the dynamic. Johnston, by contrast, embodied lesbian feminism: she delivered a poetic monologue, then orchestrated a spontaneous performance with two other women, simulating a lesbian ménage à trois on stage. Mailer was apoplectic. He’d lost control. The audience — Sontag, Friedan — watched with a mix of shock and glee. Johnston’s declaration that “all women are lesbians except those who don’t know it yet” struck a nerve. The moment was glorious, irreverent, defiant. Feminism in action. Utopia in action.

Bindel is right: lesbians model how to live without men — without their approval, their control. Her voice sings. Her joy is untarnished by the heterosexual woman’s years of adjusting to male power. If Johnson is right and all women are lesbians, they just don’t know it yet — I get it. To live one’s exuberance freely and be appreciated? To be joyful and laugh, with others who get it? It’s an intoxicating prospect.

After the Supreme Court judgment, I walked taller. The law confirmed my existence as a material, sex-based reality. If I find a man in my changing room, I can have him removed. He’s committing an offence. I have a boundary. I am a human being in the eyes of the law. That it was ever contested doesn’t matter now. We’ve come out of the rubble, blinking like survivors. Our happiness — so unfamiliar — begins to shine in our veins.

The backlash came fast. And then the fatalism. Women second-guessing their own triumph. Parliament Square fills with protesters! The government threatens to undo it! Men say they’ll ignore it! It’s as if we’re too used to losing to recognise that we’ve won.

But the Supreme Court didn’t make new law — it clarified existing law. All those HR departments, public institutions, and state-funded media have been acting unlawfully. Stonewall, who’ve misadvised them all for years, should be sued into oblivion. As Graham Linehan said in a piece in the Times over the weekend: undoing the damage is going to take a long time.

Women are uninitiated in victory and it takes a beat to really understand: this is what winning looks like. There are battles ahead, of course, because men don’t like to lose to women any more than they like to laugh at their jokes. But now is the time for full celebration. For joy. For exuberance. As Sonia Sodha said in her last Observer column:

“To the countless women who lost so much in fighting to re-establish what was supposed to be ours all along… Pop those champagne corks. Celebrate as hard as you like. You deserve it.”

Hear hear!

Ladies, exuberance is the greatest act of resistance there is. Be happy. Men aren’t women!

Thank you for reading,

Polly x

If you appreciated this week’s Monday Night Read, please do consider taking out a paid subscription which greatly helps to support me (and is 20% off for an annual subscription). Or you could buy me a coffee as a one-off hello. I consumed three in writing this piece, so every little helps!