Judgement Under Pressure

Lessons in not playing the game

Hello, I’m Polly Clark, novelist and TS Eliot Prize–shortlisted poet. Monday Night Reads brings thoughtful writing direct to your inbox every Monday at 7pm. Recent highlights include my interview with Graham Linehan and my essay Reality, Delayed about being stranded in a hotel listening to Helen Webberley.

If you value my work here, please consider a paid subscription or buying me a coffee. Your support makes all the difference and keeps this space alive. My latest novel Ocean is out now. My poetry retrospective, Afterlife: New and Selected Poems is published February 2026.

Dear Reader,

Most days I walk a varying circuit of my marina and the surrounding parkland, surrendering my thoughts to the wintry magic of the skyscrapers of Canary Wharf, the austere patrol of the swans around Greenland Dock, and the sweep of the Thames itself. Some days the river gallops out to sea so fast it rattles the floating platform at the pier; sometimes it has the greasy slowness of near-frozen water, neither liquid nor solid, an in-between form for a time of hibernation.

As I walk I listen to music, but this week I’ve been listening to Finding Endurance: Shackleton, My Father and a World without End by South African writer Darrel Bristow Bovey. And on my walk yesterday I was jolted out of my surroundings by what I was hearing. I stopped dead in the park and began to write things down.

Ernest Shackleton was a poet before he was an explorer. He published some apparently not very good poems under the pseudonym Nemo (which means ‘nobody’). Becoming an Antarctic explorer was, it seems, a displacement activity for a deeper calling, what Poe calls: ‘The irrational pursuit of a terrible incommunicable knowledge’. The Southern Pole is truth without consolation. There are no landmarks, no polar bears, no meaning. Just a desolate plain atop a frozen mass. The closest we might get to outer space upon the Earth.

It is a place that strips purpose down to endurance alone. To seek a truth such as this demands not adventuring spirit, but vocation. Such a commitment will estrange you from ordinary reward systems. No wonder I stopped and sank onto a bench.

Ernest Shackleton and Robert Falcon Scott both aimed for the Pole, and both failed in different ways. Scott reached it, only to discover he had been beaten there by the Norwegian team, and he and all his companions died on the return journey. Shackleton never reached the Pole at all, but he brought every one of his men home. You might be forgiven for thinking Scott therefore “succeeded”: he is memorialised in the popular imagination as ‘Scott of the Antarctic’, after all. His version of sacrifice for an ideal has been retrofitted as success. His death could be absorbed by the culture that sent him; it confirmed, rather than disrupted, the values that put him there. But it would be more accurate to say that Scott died serving a definition of success that could not sustain life. Shackleton, by contrast, redefined success when the old definition became meaningless. Under pressure, he exercised judgement about what was ultimately true. There’s a poet for you.

Scott and Shackleton were rivals for the Pole. Scott was an establishment figure, the chosen explorer of the Royal Geographical Society. Shackleton’s Irish heritage marked him out as not belonging. Class, as ever, was the immutable structure within which all things unfolded. Though Shackleton was likeable and popular, these very qualities irked the establishment and Scott in particular. Even the King, who endorsed the outsider’s expedition, urged him to ‘play the game’. However, this was impossible for Shackleton, because you can’t learn the rules of the game. You only belong if you already know them.

Though Scott could not prevent his rival’s attempts, he demonstrated his sense of entitlement by extracting a promise that Shackleton would not land in the McMurdo Sound, the southernmost passable sea and the critical gateway into glacial waters. Scott pre-emptively claimed the Sound as ‘his’. That rapaciousness — and the fragility it revealed in the face of a challenge from an outsider — feels familiar more than a hundred years later. When conditions grew impossible during his attempt on the Pole, Shackleton broke the promise. The ability to exercise judgement, and to prioritise survival, would remain threatening to institutions and individuals who valued winning ‘the game’ above all else.

In a quieter example of Shackleton’s judgement, Bristow Bovey relates the story of how Frank Worsley became Captain of Endurance. In his diary Worsley writes that he had a dream one night that all the streets of London that were so familiar to him became covered in ice. It was so vivid that the next day he walked those same streets of his dream, and in so doing came across a sign inviting sailors to apply to join Endurance’s expedition. He immediately went in and told Shackleton his dream — and was hired as Captain on the spot.

Shackleton was someone who understood imagination as a practical skill, intuition as a necessary component of survival, and dreams as instruments of judgement. He trusted someone who wandered in and spoke from that place. He made a decision outside formal criteria, and in so doing showed his understanding of the magnitude of what he was undertaking. If you are going to survive a pilgrimage to the ‘awful place’, as Scott put it, you had better recruit your crew from the fearless dreamers and the poets of the practical.

That way of proceeding is not confined to polar history. Expeditions of a type have marked my own life, for reasons that were not wholly clear to me at the time. There was a journey to Siberia to track tigers, to a remote region which until recently was inaccessible without a permit. There was a crossing of the Bay of Biscay as crew, undertaken to understand sailing and to feel the vastness of the ocean. There was a one-way ticket to the Balkans with just a Rough Guide and a mispronounced vocabulary of three words: igen, nem and köszönöm. And latterly, the decision to leave a familiar life in order to live on a boat in London. Seen in isolation, these might be described as mildly eccentric research. Taken together, I think we can agree they form a pattern.

Others recognised the pattern before I did. A friend described me as an adventurer; others have reached for different images: a bird, a butterfly, someone who longs to be free above all else. These descriptions were generous, and I received them as such, but I misunderstood what they were pointing to. From the outside, my choices looked, even to me, like an appetite for risk. From within, they felt more like obedience to something exacting.

That distinction helps to explain my relationship with London itself. I recently read Julie Burchill writing about the city as a place she once belonged to so fully that she can now live elsewhere without loss. Many of my contemporaries describe a glittering London of the nineties that still feels like home to them. But that London was never mine. I also lived in London in the early nineties and worked in Soho. I was part of the long liquid lunch culture, downing innumerable pints at the Coach and Horses while Jeffrey Bernard clung to life at the end of the bar. But I was slaving in an office above Madame Jo Jo’s, writing porn for Paul Raymond and peeping out of my windows at the celebrities wandering down Brewer Street. I didn’t even know they were celebrities until my colleagues rushed to the window to point out this person or that.

What I lacked was not appetite or nerve, but a framework in which my efforts made sense. I had taken an enormous leap to get to London, but I did not understand how status accumulated, how visibility converted into security, or why some kinds of work led somewhere while others did not. Or perhaps I sensed these things dimly at the time and was already exercising judgement under pressure — engaged in survival rather than in striving for the Pole. Perhaps I was already seeking something else.

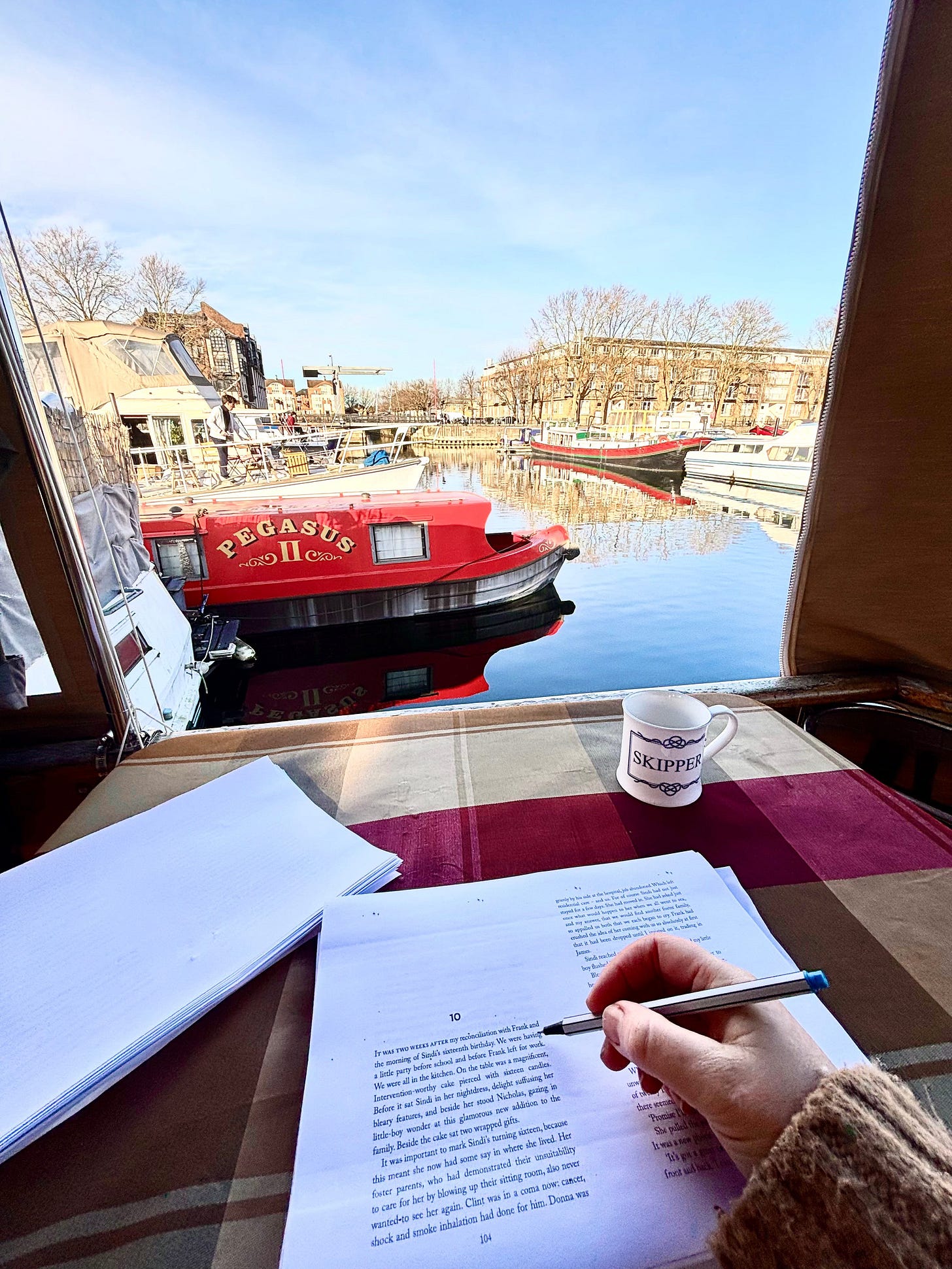

Many years later I have made the expedition to London again. I have a home here (all those years ago I lived chaotically with my estranged father). Crucially, a boat means I am both here, but not here; her beauty and history laid out before me, but not mine to own, and I, too, am free-floating. London was for so long defined for me by a few key people who knew me there and then, and who for one reason or another are no longer present. I am learning, tentatively, how to occupy it in my own way.

The truth, for me, is something to be arrived at, over as many attempts as it takes, and in whatever manner works. Shackleton understood imagination as an expedition tool, and survival as a form of success. If, for now, I stay aboard and observe rather than disembark much of the time, this is not fear, nor lack of curiosity. It is judgement under pressure.

Thank you for reading,

Until next time

Polly x

If you have enjoyed this week’s essay, do please consider taking out a paid subscription or buying me a coffee. I really appreciate each one. A big welcome to those who have joined me recently. And a special thank you, to those of you who have renewed your paid subscription.

Saturday Writing Cabin (pilot)

I’m trialling a quiet, no-frills writing hour on Zoom:

Saturday, 31 January 2026, 10–11am.

We arrive, we work, and we wave goodbye.

Hour by hour is how I write essays like today’s, as well as all my novels and poetry. If that is how you work too — or if you’d like to form the habit — you are welcome to join me.

Hour Club members are welcome to attend for free (booking still required).

For others, tickets are £4.

This is a pilot. If it works, I’ll repeat it.

Tiger is a book I absolutely love for its extremes. 🐅

That’s really interesting about Shackleton! It doesn’t surprise me, however: I think the polar extremes communicate something to the poetic parts of us all. I find it difficult to resist a book with a snowy or icy cover, and often get my pupils to use winter as an extended metaphor in their creative writing. Great essay, thanks. ❄️

I recently enjoyed a light read which touches on the Arctic expeditions - A Woman Made of Snow by Elizabeth Gifford - so is thus your next adventure/novel? 😉